Recovering Metadata from .NET Native AOT Binaries

Ever seen a binary that looks like a .NET binary based on its strings, but .NET decompilers are not able to open them?

You may just be dealing with a Native AOT binary!

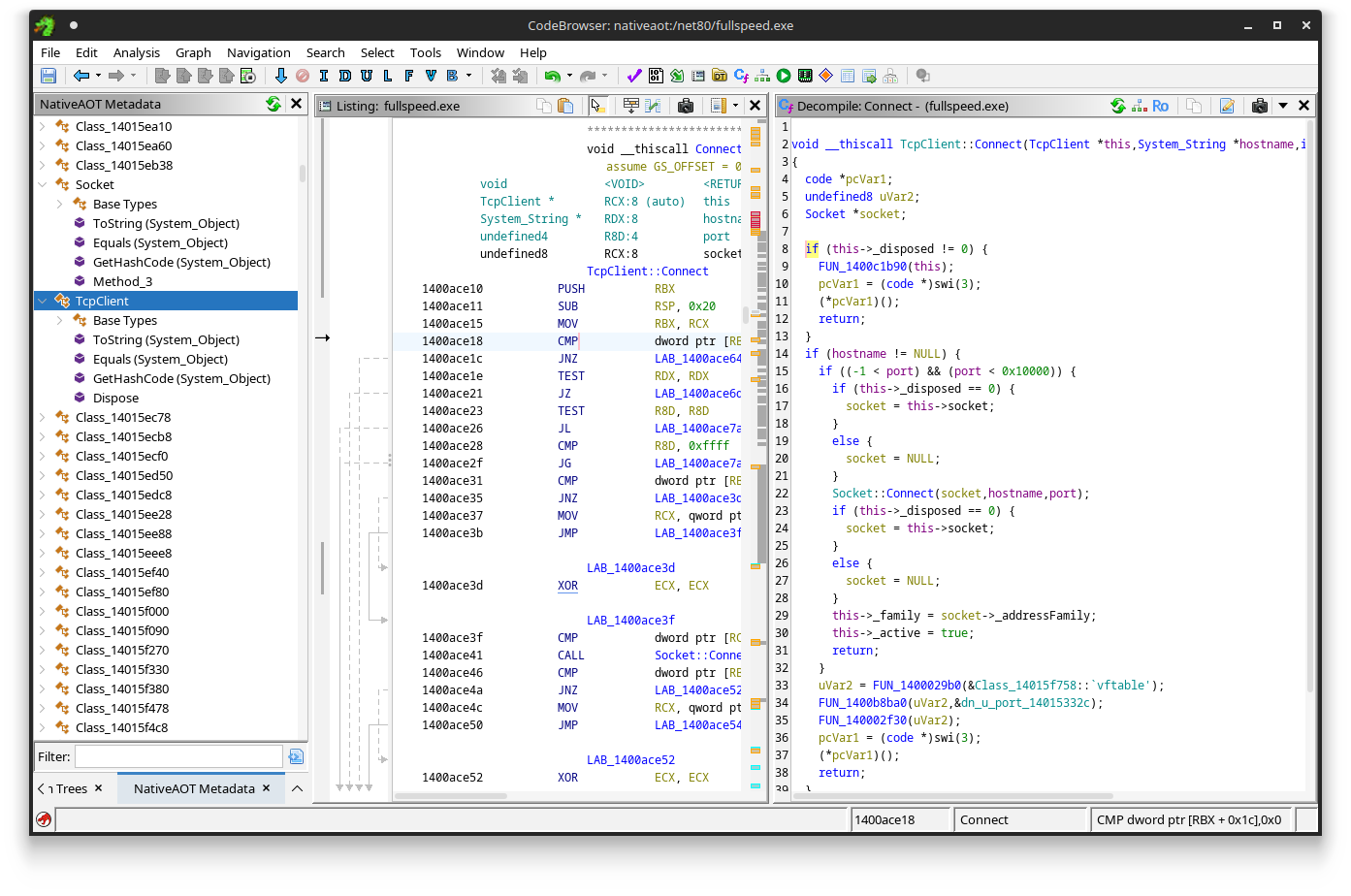

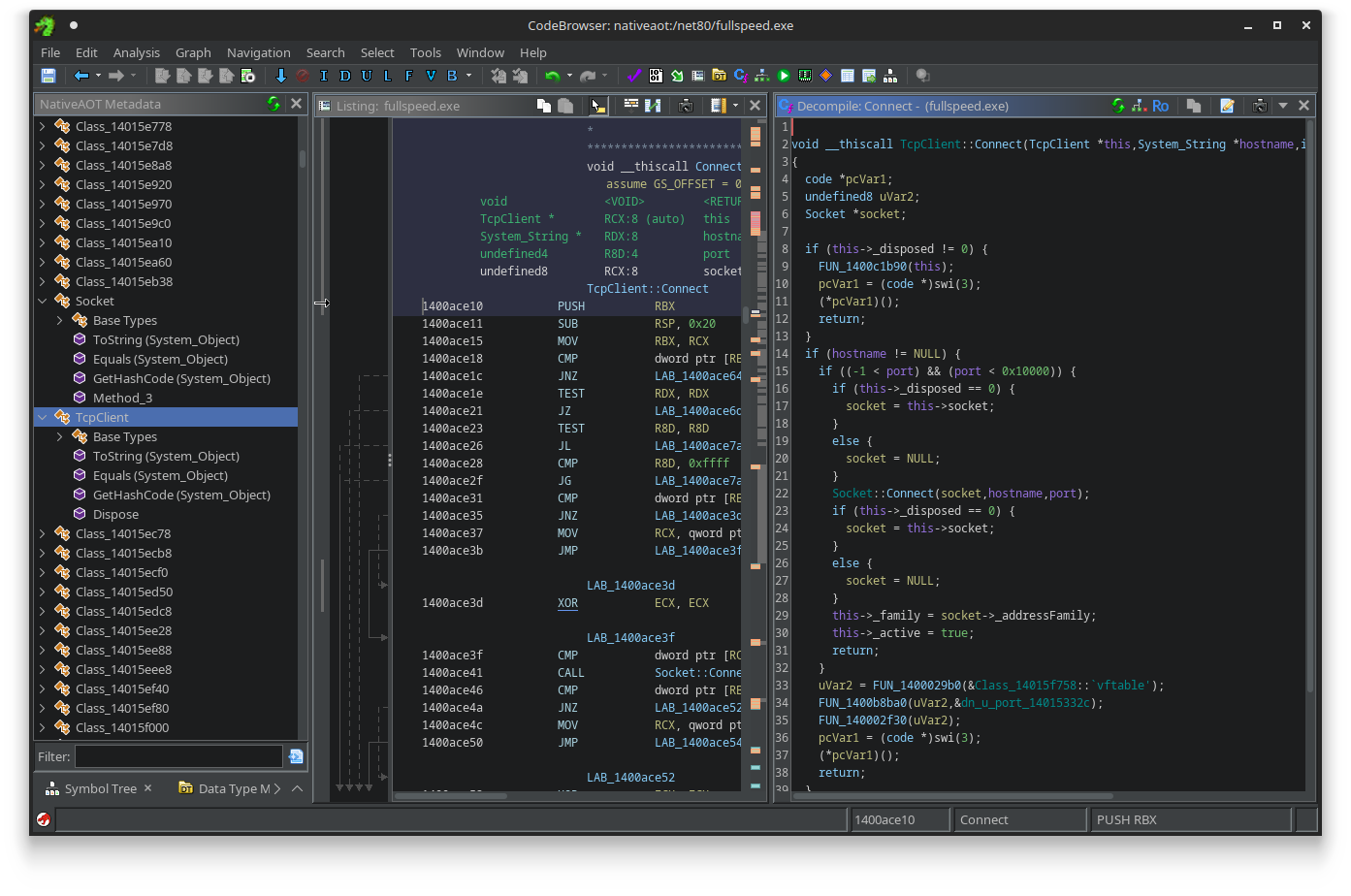

That may sound scary, native decompilation is much harder than .NET decompilation. However, what if you could make Ghidra look like this:

In this post, we will discuss Native AOT - Microsoft’s latest Ahead-Of-Time Compilation Technology - in great detail from a reverse engineering standpoint. We’ll talk about what it is, what it looks like in a general purpose decompiler, and how we can (automatically) extract this metadata to reconstruct most of the original type hierarchy. As it turns out, a lot of the metadata is actually still intact, provided you know where to look!

If you are just interested in the tool that automates (almost) everything discussed in this post, scroll down to Ghidra Plugin or hit the button below to download it.

What is Native AOT?

In 2022, Microsoft released .NET 7. It came with many features and performance improvements, and one of these features is Native AOT deployment.

Traditionally, applications written in a .NET language (e.g., C# or VB.NET) are not compiled directly to native machine code (e.g., x86 or ARM), but instead compile to an intermediate bytecode (CIL). This bytecode is then dynamically compiled to native code at runtime using a Just-in-Time (JIT) compiler.

Similar to Java, this is great for portability as it allows a developer to only compile their program once without having to worry about user base coverage. As long as the user has the .NET runtime installed (.NET Framework 4.8 is installed by default on Windows 10+), they will be able to run the program fine.

One downside however is that it requires the JIT compiler to always rerun the same compilation step every time the program is executed. For long living applications (such as server applications), this is not a big problem, but for smaller short-lived applications (e.g., command line tools) this can introduce noticeable startup times. Therefore, in .NET 5, Microsoft introduced a new form of compilation called ReadyToRun (sometimes referred to as RTR or R2R). Similar to a normal build, ReadyToRun compiles your .NET application to CIL, but also pre-JITs all the bytecode at compile-time in advance. The generated native code is then shipped alongside the CIL code, allowing the program to skip the JIT process at runtime when running on supported hardware.,and revert to JIT when it does not.

While this is a significant improvement, it still does not fully get rid of the runtime, which still needs to be loaded on every startup. This is where Native AOT deployment steps in. Being the spiritual successor of ReadyToRun, Native AOT compiles the binary into a fully native executable, and statically links all the standard libraries and dependencies. This fully gets rid of the JIT compiler and thus slow startup times, and often also results in a much smaller memory footprint as a nice bonus.

A great win for performance, at the cost of some compatibility.

Reverse Engineering Native AOT Binaries

However, an interesting side-effect is also that it can act as a first-party obfuscation engine.

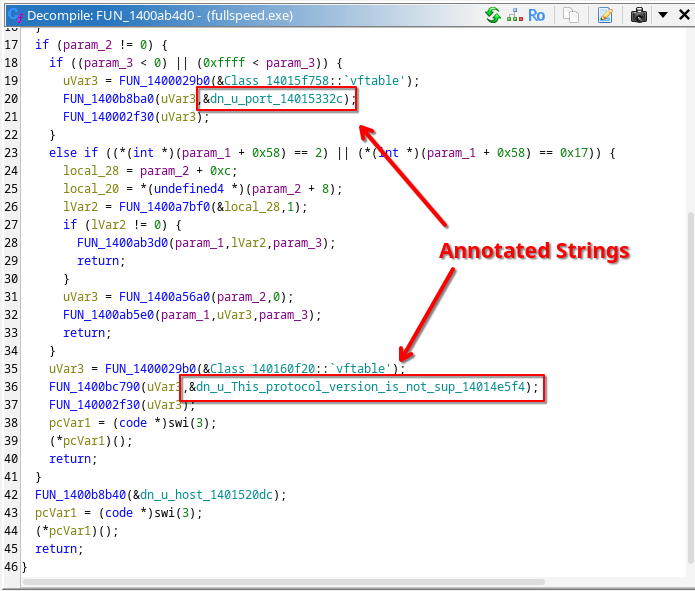

Traditional .NET binaries are relatively easy to decompile, as they contain a lot of metadata about defined types and their defined fields and methods. This makes it almost trivial for tools like ILSpy to get an unprotected .NET binary to a near perfect source code representation that is recompilable.

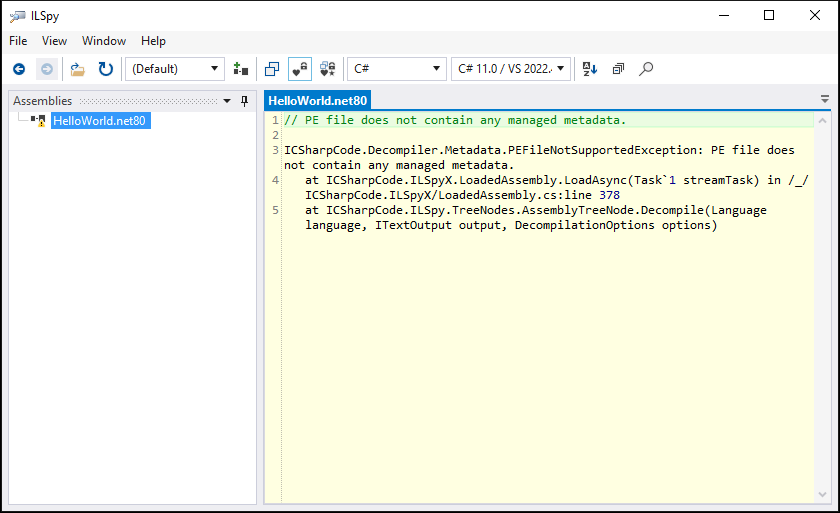

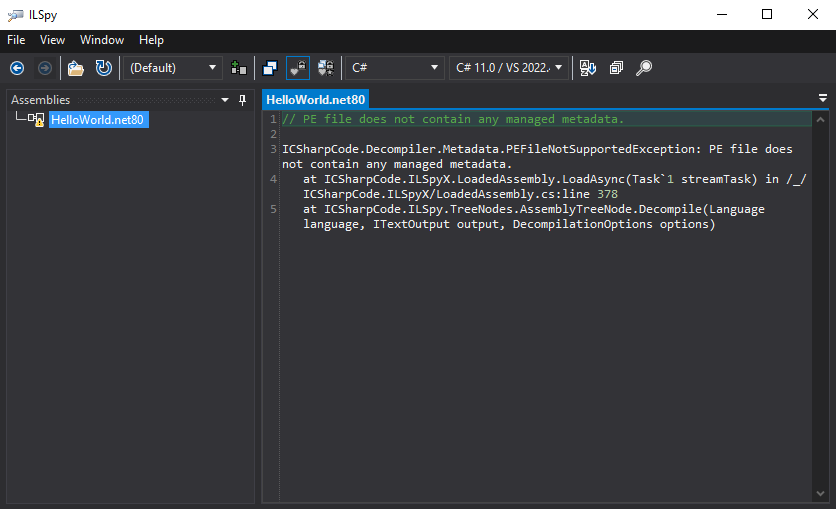

.NET decompilers can decompile almost perfectly normal CIL binaries.

.NET decompilers can decompile almost perfectly normal CIL binaries.

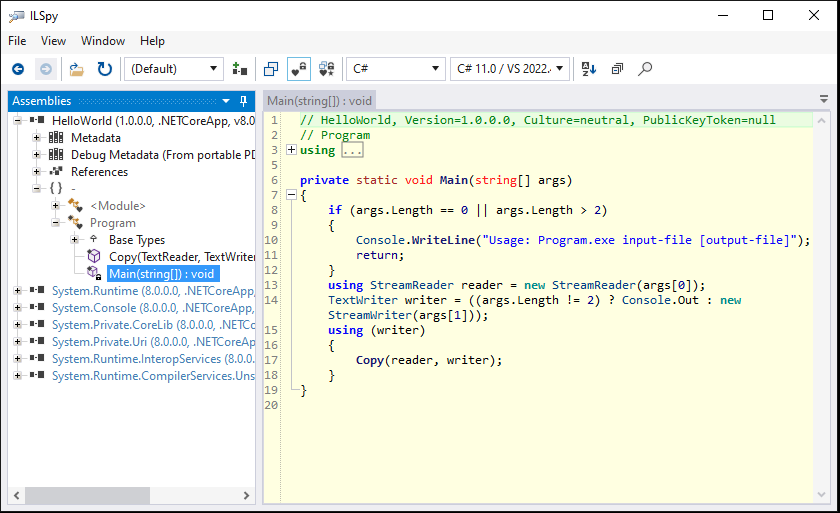

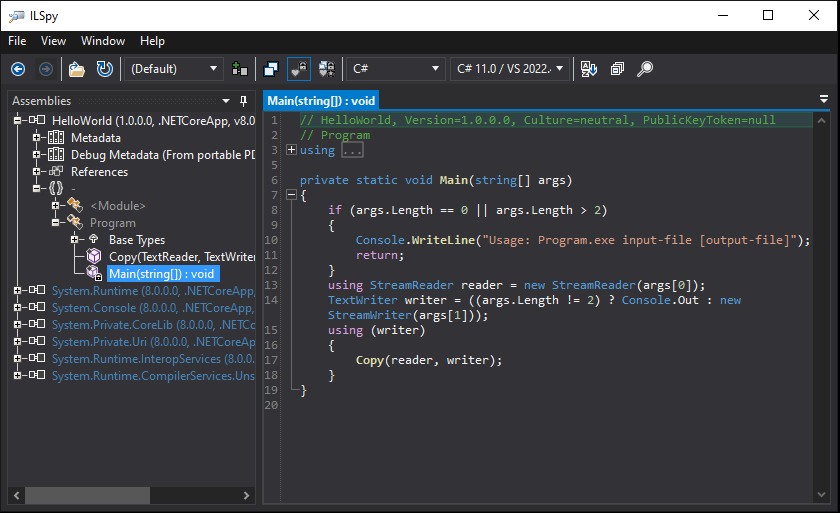

To this end, (malware) developers have been (ab)using various obfuscators, free and commercial, including products like SmartAssembly, .NET Reactor, ConfuserEx and all its derivatives. But now with Native AOT, you can just compile your binary with no trace of bytecode to be found nor a runtime to hook into with e.g., WinDBG or dnSpy:

.NET decompilers don’t know how to work with Native AOT binaries.

.NET decompilers don’t know how to work with Native AOT binaries.

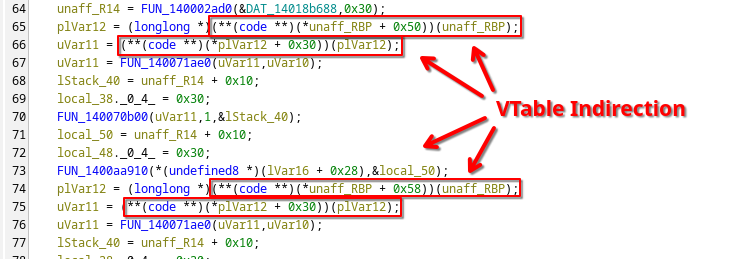

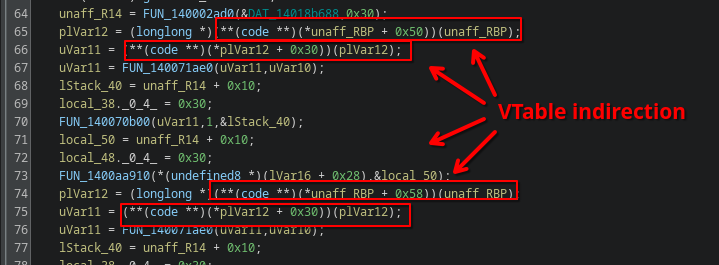

You can open the binary in a tool like Ghidra or IDA, but these binaries are massive as they also include code of all the required standard libraries. To make matters worse, since .NET facilitates an environment that operates on objects with inheritance and other Object Oriented Programming (OOP) related concepts, Native AOT binaries closely resemble compiled C++ binaries with lots of VTable pointer indirection.

This effectively turns the compiler itself almost into an obfuscation engine, as it is incredibly laborious to make sense of it all in the end.

Metadata Rehydration and Recovery

So is all metadata lost after Native AOT deployment?

Not quite! Recall that the original program still was written using a .NET language. This means that some type information must exist, e.g., to implement the rules of runtime type checks, inheritance and interface dispatch.

In fact, a lot of metadata about the original type hierarchy is actually fully intact. The only thing we really need to find is something known as the ReadyToRun directory.

“ReadyToRun? I thought this was Native AOT?”

And you would be right!

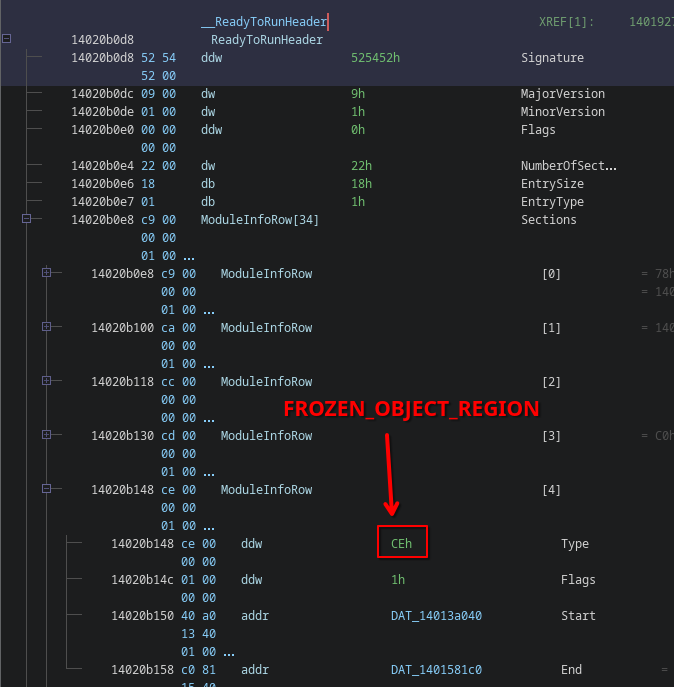

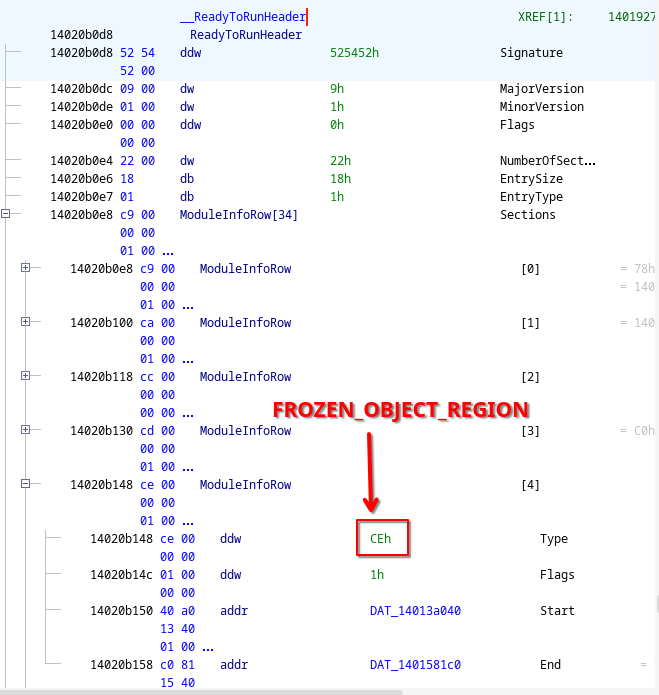

However, Native AOT is heavily inspired by ReadyToRun. As such, many of the structures are very similar if not equivalent. Each Native AOT binary defines at least one ReadyToRun directory (and from my testing in practice this number is exactly one, though it is technically possible to have multiple).

Its physical structure is defined as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

struct ReadyToRunHeader

{

uint32_t Signature;

uint16_t MajorVersion;

uint16_t MinorVersion;

uint32_t Flags;

uint16_t NumberOfSections;

uint8_t EntrySize;

uint8_t EntryType;

// Array of sections follows.

};

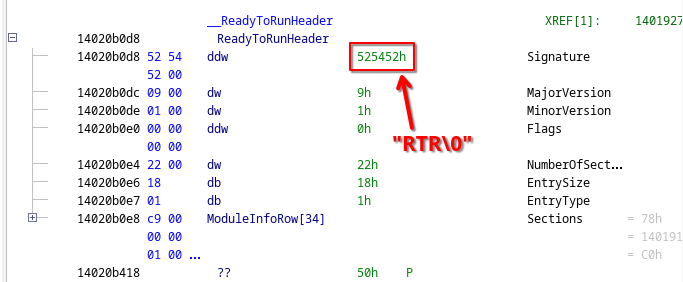

ReadyToRun directories can be recognized by their distinct signature "RTR\0":

Data Rehydration

The ReadyToRun directory contains many tagged data directories, with all kinds of metadata to make things work.

Most of them are not that interesting to us.

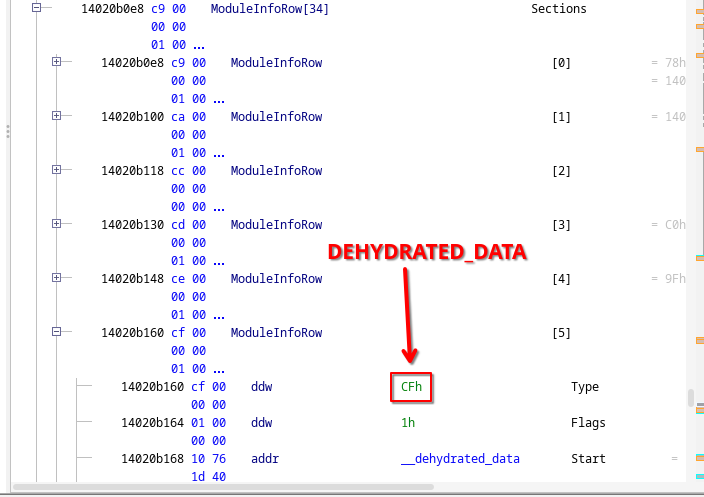

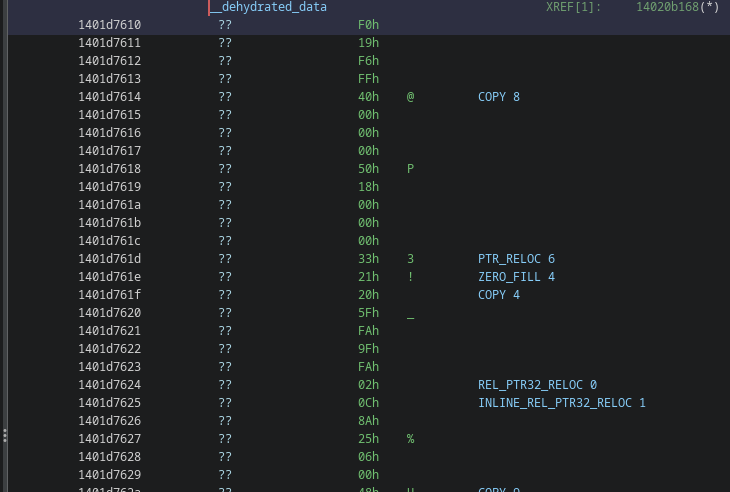

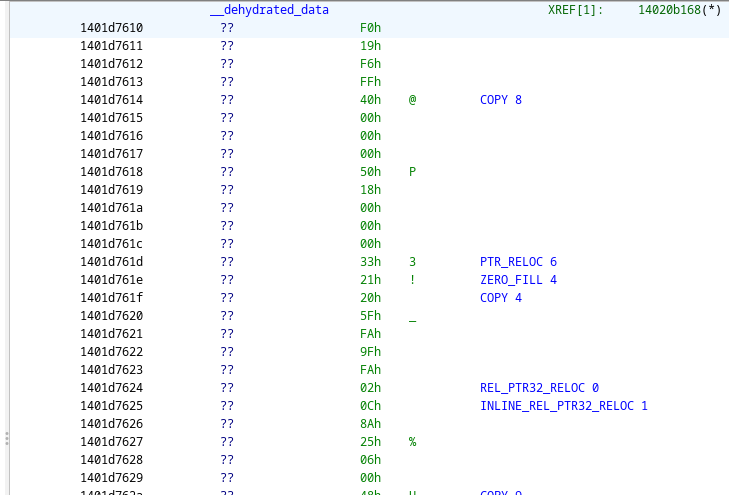

However, one of these sections has the tag 0xCF (DEHYDRATED_DATA):

Dehydrated data contains all the information we need to reconstruct most of the metadata. It is a huge blob of compressed data that at runtime is decompressed (rehydrated) in some virtual memory. It consists of three segments:

- A 32-bit header containing the relative offset of the output buffer (hydrated data section).

- The compressed (dehydrated) data.

- A fixups table of pointers and deltas.

By default, .NET 8 puts the decompressed data in a separate virtual section called hydrated.

.NET 9 does not define a separate section, but the format has remained the same.

The compressed (dehydrated) data itself is a sequence of instructions that build up the hydrated data by repeatedly writing into the destination buffer.

The fixups table is used to efficiently store pointers and offset deltas.

Every instruction uses the first 3 lower bits to specify its opcode. Depending on the opcode, an operand may be present in the remaining bits of the opcode and in the bytes after it. There are six different opcodes (see also DehydratedData.cs):

| OpCode | Mnemonic | Description |

|---|---|---|

0x00 |

Copy |

Copy the next n bytes into the output buffer. |

0x01 |

ZeroFill |

Write n zero bytes.. |

0x02 |

RelPtr32Reloc |

Write a pointer from the fixup table as a 32-bit relative operand. |

0x03 |

PtrReloc |

Write a pointer from the fixup table as an absolute address. |

0x04 |

InlineRelPtr32Reloc |

Write a list of 32-bit relative operand pointers. |

0x05 |

InlinePtrReloc |

Write a list of absolute addresses. |

Therefore, to rehydrate the section and get the data as it would appear at runtime, we need reimplement these opcodes, decode all instructions in the dehydrated data, and simulate the same execution semantics as described in the above (see also StartupCodeHelpers.cs).

Decoded rehydration instructions.

Decoded rehydration instructions.

Method Tables

In the decompressed (rehydrated) data you can find a lot of things, but for us, the most important data structures right now are the Method Tables.

Physical Structure of a Method Table

A Method Table (MT) is the underlying data structure of a type defined in a .NET module. It is very similar to a Virtual Function Table (VTable) that you can find in C++ compiled binaries, but with a few modifications. Each MT roughly has the following structure (simplified, see also MethodTable.h):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

struct MethodTable

{

uint32_t m_uFlags;

uint32_t m_uBaseSize;

MethodTable* m_RelatedType;

uint16_t m_usNumVtableSlots;

uint16_t m_usNumInterfaces;

uint32_t m_uHashCode;

/* void* VTableSlots[m_usNumVtableSlots] */

/* MethodTable* Interfaces[m_usNumInterfaces] */

};

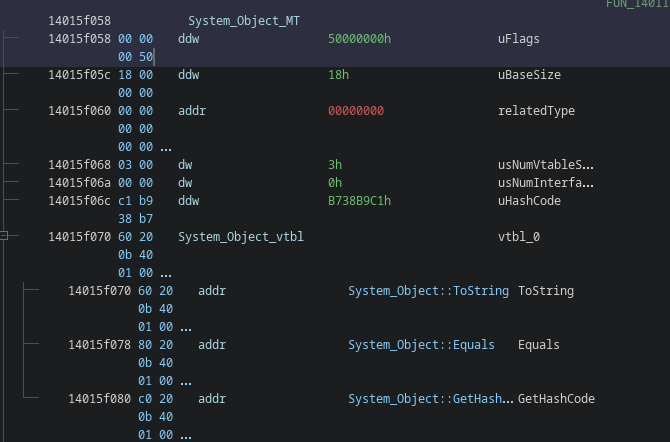

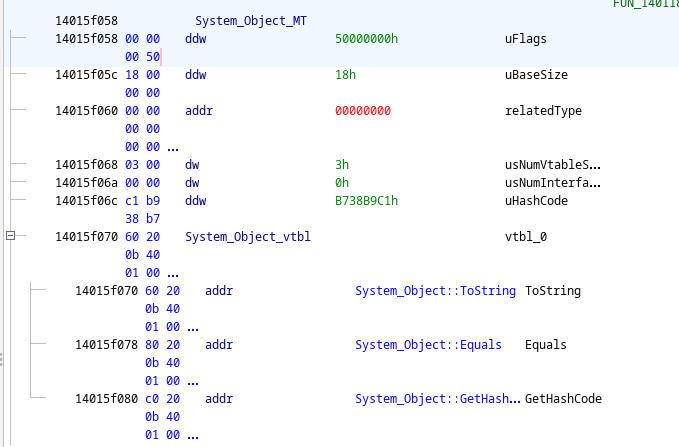

The first couple fields are all metadata, similar to normal metadata in a .NET binary, with some nice additions that are pre-computed at compile-time:

m_uFlags: Specifies the element type (e.g., class or valuetype) and a few other properties.m_uBaseSize: The minimal size that each instance of this type occupies in memory.m_RelatedType: This is in most cases a pointer to the direct super class (sometimes referred to as base class) of the type. For arrays and other type signatures, this is their element type.m_usNumVtableSlots: Number of slots in the VTable.m_usNumInterfaces: Number of interfaces that this type implements.m_uHashCode: Not important for our use-case.

After the metadata fields, the actual VTable slots follow.

This is an ordered list of function pointers that point to the implementation of the method that is used for this particular type.

Note that this therefore means it will also contain pointers to methods of each base class, even if they hadn’t been overridden by the class.

Effectively, this implies that every (non-interface) type has at least three VTable slots allocated for System.Object’s methods (i.e., ToString(), Equals(object) and GetHashCode()).

This will be important later.

Finally, after the VTable slots, there is a list of pointers pointing to the method tables of all the interfaces that this type implements.

Technically, there is some more data after the interfaces, but this is out of scope for this post.

Finding the Method Table of System.Object

Let’s start simple and find the Method Table of System.Object, the root of all types in .NET.

Recall that System.Object is roughly defined as the following in C#:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

namespace System;

public class Object /* No base type */

{

/* ... */

public virtual string ToString() => /* ... */;

public virtual bool Equals(Object other) => /* ... */;

public virtual int GetHashCode() => /* ... */;

/* ... */

}

This is what its MT looks like:

We can observe some key features here that make it very distinguishable from other MTs:

- Its

m_uFlagsfield only has theCLASSbit set (i.e., its raw value is set to0x5000_0000) - It has exactly three non-zero VTable slots (for its virtual but not abstract methods

ToString,EqualsandGetHashCode). - It has no interface slots (i.e.,

m_usNumInterfacesis set to0). - Its

m_RelatedTypeis set to0x0000_0000(i.e., it does not have a super class, meaning the VTable slots must be freshly introduced).

Additionally, as System.Object is the root of all types (except for interfaces and canon types), there will be lots of classes that directly inherit from this class, and thus their m_RelatedType field will directly reference this exact data blob.

Since we can simulate the rehydration algorithm, we also know every pointer that is written to the output buffer.

Thus, for every pointer the rehydration algorithm writes to the hydrated output buffer, we can check if points to a structure that looks like this, and make a guess this is indeed System.Object.

I’ve ran this idea over various .NET Native AOT binaries, and from my testing these criteria have always resulted in exactly one candidate MT for System.Object, which leads me to believe this is sufficiently robust to be able to reliably identify System.Object.

Success!

Finding All Method Tables

Once we’ve found System.Object we can extend this idea to recover the entire type hierarchy.

We can iterate over all pointers in the hydrated section a second time, and see if they point to any currently known MT.

If it is, there is a decent chance this pointer is the contents of the m_RelatedType field of another MT (at offset +8), which means we can add it to our pool of known MTs:

Once we’ve gone over all pointers, we can simply repeat the process to discover more MTs:

Additionally, every MT that we introduce may also define a list of pointers to other interface MTs that we hadn’t recovered before either. We can add those to the pool as well.

Repeat this process until no more method tables are found.

It is not guaranteed however, that every pointer to an MT is in fact a m_RelatedType.

The rehydrated data also contains other data (such as frozen objects, more on that after this), but we can try to interpret the data around it as an MT, and check that it doesn’t look too weird (e.g., it has a reasonable number of VTable slots and interfaces implemented).

If it is too much out of whack, we add it to an exclusion list to not consider it ever again as an MT.

Frozen Objects and Strings

Now that we have identified all MTs, we can also identify frozen objects stored in the hydrated data.

Frozen objects are instances of specific types that are initialized and serialized at compile-time, such that they are ready for use at runtime.

Good examples of frozen objects are static readonly fields and constants like string literals.

Frozen objects reside in a separate subsection of the hydrated data, which is referenced as a ReadyToRun section tagged with 0xCE (FROZEN_OBJECT_REGION):

Physical Layout of an Object

Every object (both dynamically created at runtime as well as frozen at compile time) in .NET roughly has the following structure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

struct Object

{

/* void* gcInfo; (at offset -8) */

MethodTable* mt; /* <-- this is where each object reference points to. */

/* ... Object data ... */

};

Each object reserves one pointer-sized field for GC information, which is then immediately followed by the MT representing the type of the object. This MT is used to implement all object-oriented related concepts at runtime, including runtime type-checks and method overrides.

After this header, the actual object data (i.e., its fields) are stored, which is aligned to the next pointer-size byte-boundary.

You will thus find that m_uBaseSize field in every MT of a 64-bits Native AOT binary is almost always set to 24 bytes (0x18) or larger: 8 bytes for GC info, 8 for the MT, and at least 8 for its contents (even for empty classes that do not define any fields like System.Object).

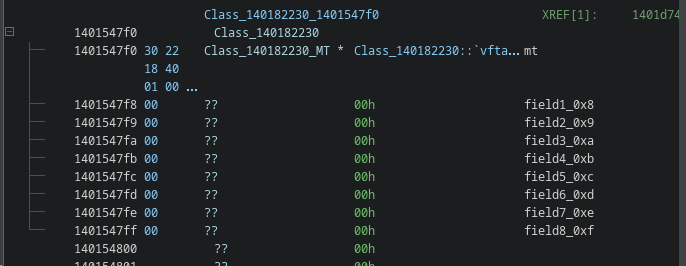

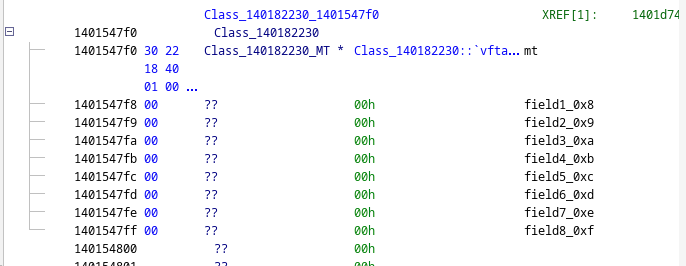

A typical example of a frozen object of type can be seen below.

You can clearly see it starts with a pointer to its method table (Class_140182230), directly followed by its contents (fields):

You may be wondering why is gcInfo commented out in the definition of Object in the above.

This is because every pointer to an object actually does not point to the start of the object, but instead to its MT field (presumably for performance reasons).

This means GC info actually appears at offset -8 of each object reference, which cannot be represented in normal C.

String Literals

The above holds for every instance deriving from System.Object.

However, strings are kind of the exception to this rule.

If we look at the definition of System.String, we find that its internal representation looks a bit like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

namespace System;

public sealed class String : Object

{

private int _length;

private char _firstChar;

}

You may have expected a string to store all characters in an array or perhaps a char* pointing to the first character of the string.

Instead, we see _firstChar being defined as a single char instance.

This is because strings are composed and do not have a fixed size.

.NET actually implements some special logic where the actual contents of the string is put right after its _length field.

This means that _firstChar field definition can be used to get the address of the first character of the string, without having to allocate it somewhere else or having to dereference a secondary pointer.

1

2

string myString = "...";

char* stringData = &myString._firstChar;

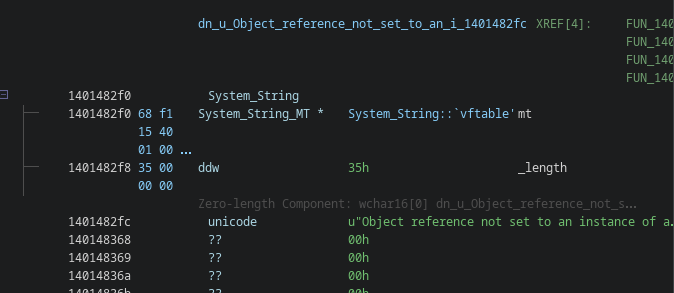

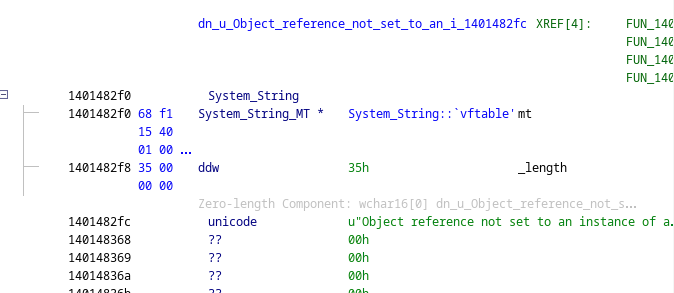

This also means, from a reverse engineering standpoint, that if we encounter a frozen object of type System.String, then its actual contents will be right after the first field.

To identify frozen System.String objects, we can use again a similar trick to identifying System.Object, as string objects will reference an MT with a very distinguishable shape:

- Its

m_uFlagswill have theCLASSbit set. - Its

m_RelatedTypeis pointing to the MT ofSystem.Object(which we have already identified at this point). - Its

m_uBaseSizewill actually have an unaligned value of0x16instead of0x18(GC info + Method Table + 4 (sizeof(_length))).

As it is not possible for other non-composed types (which is every other user-defined type) to have an unaligned size smaller than 0x18, this is a very strong indicator.

Once the MT of System.String is identified, we can simply go over all pointers again in the hydrated data, check if it points to this MT, and interpret the data after it as a System.String object.

Ghidra Plugin

I implemented all the ideas described in the above in a single ready-to-use Ghidra plugin over the course of a couple spare weekends, and added a few extra niceties to improve some of the UX.

For the moment, it assumes either the __ReadyToRunHeader symbol or the __modules_a and __modules_z symbol pair to be present and annotated in the binary to locate the necessary structures.

If your binary does not have symbols, these can be easily identified by pin-pointing the call to InitializeModules.

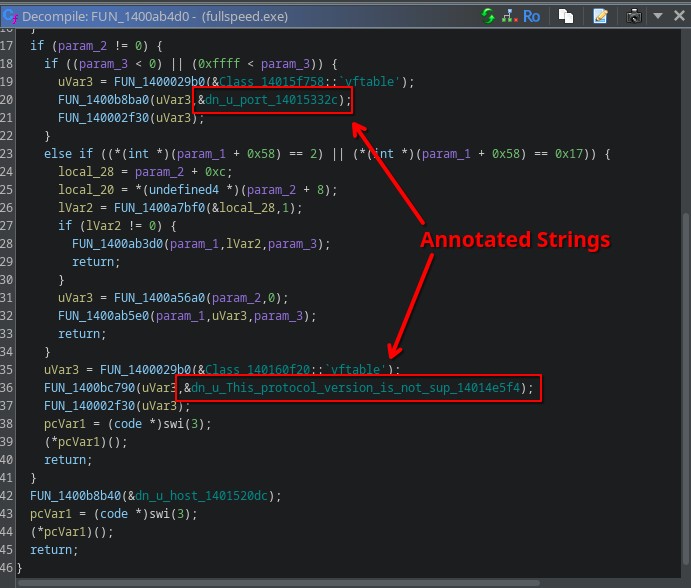

An example of identifying this call can be found below:

I don’t know enough yet about Ghidra’s API to automatically recognize this call and extract its arguments, so you’ll have to do this manually for now. Sorry!

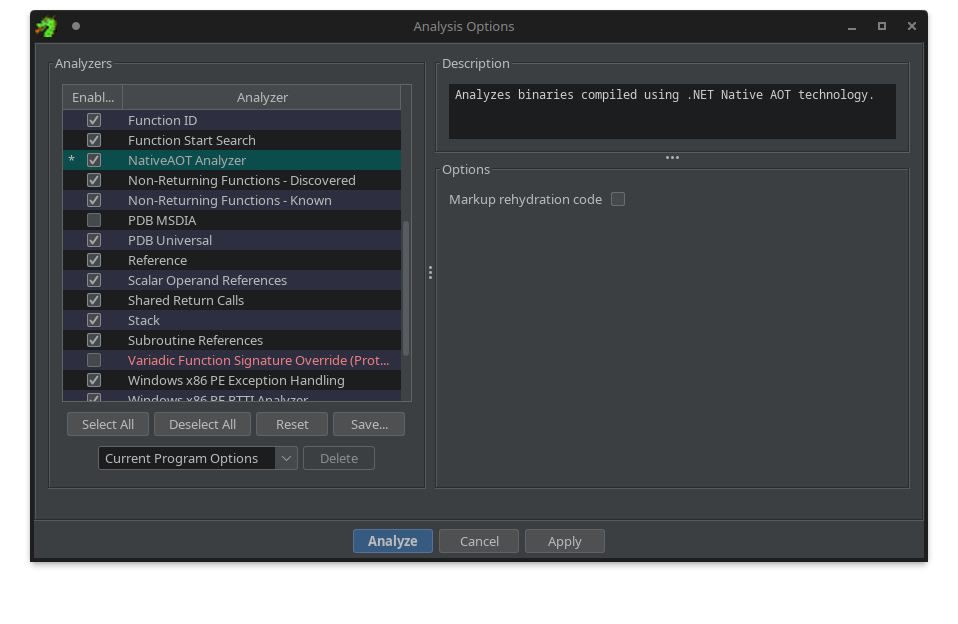

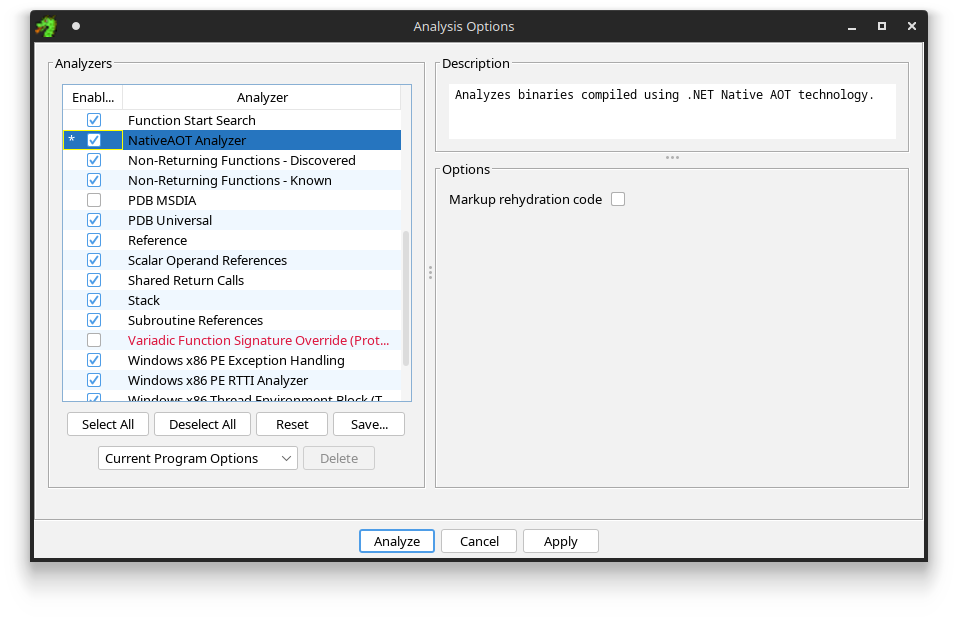

Once you have labeld the ReadyToRun directory, you can run the new NativeAOT Analyzer found in the Auto Analysis menu, or trigger it via a One Shot Analysis instead:

Trigger the NativeAOT Analyzer

Trigger the NativeAOT Analyzer

This will rehydrate the dehydrated data, find all Method Tables, define the appropriate type definitions, and annotate all frozen objects (e.g. strings).

Metadata Browser

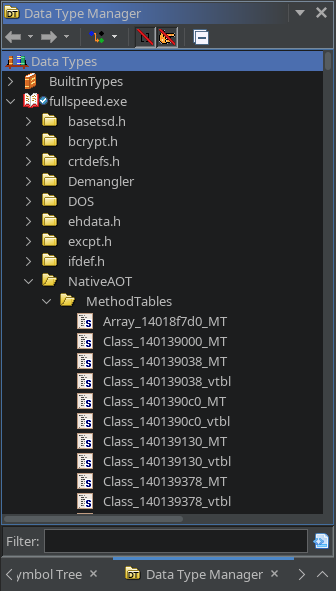

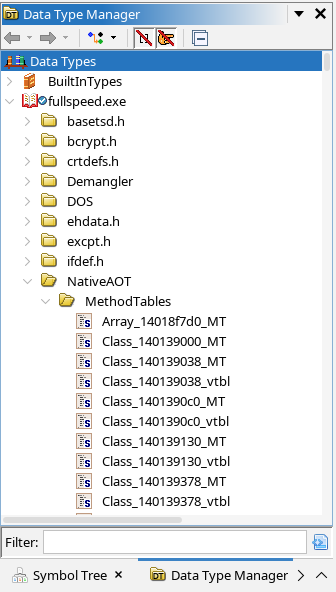

To make navigation between different types and their methods easier, I added a metadata browser pane similar to the ones found in traditional .NET decompilers:

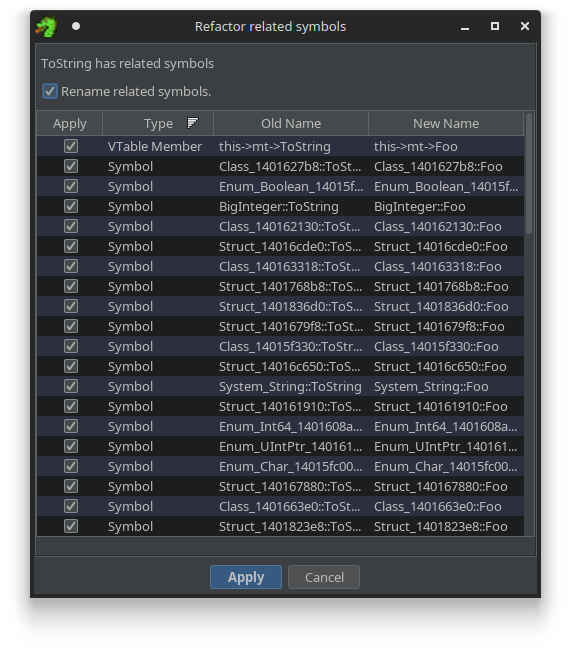

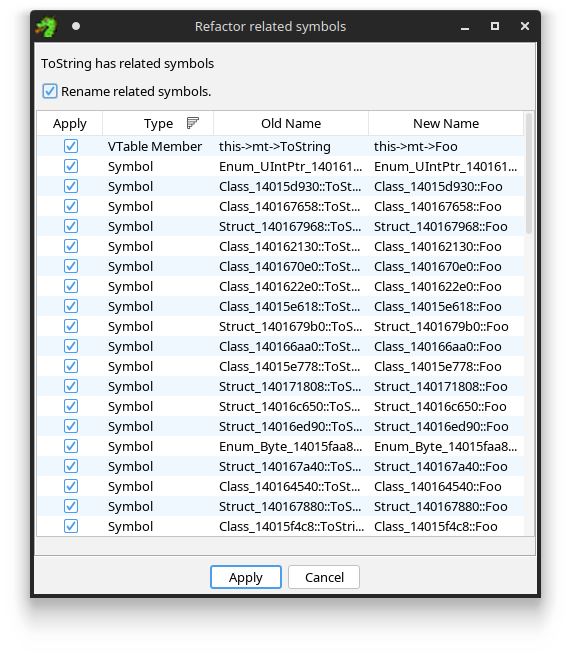

You can rename individual methods in this symbol tree, and the plugin will try to suggest renames for all the functions that implement this method.

Refactoring a symbol will suggest related refactorings.

Refactoring a symbol will suggest related refactorings.

Note that refactoring is still quite rudimentary and sometimes may not always suggest things correctly. If it is too annoying/buggy, it can be disabled in the tool options window under the new NativeAOT directory.

Method Table and Object Type Definitions

Under the hood, to keep track of everything, the plugin adds a special NativeAOT folder in the data type manager of the Ghidra project, where it persists all the type information in the form of Ghidra structure definitions.

- It defines a type for each Method Table itself (suffixed with

_MT). - It may introduce a VTable chunk type (suffixed with

_vtbl), which explicitly defines the newly introduced VTable slots if there are any. - Finally, it defines a type for each Method Table instance, with a size based on the base size determined by the MT, and pre-populates the the contents of this type with one field pointing to the underlying method table.

The underlying Native AOT type directory.

The underlying Native AOT type directory.

It also adds class symbols, and moves all functions it identified to be part of a specific class into it.

A nice bonus of doing it this way (instead of e.g., adding some additional files or metadata to the Ghidra project) is that people can still open a shared Ghidra project specifically analyzed with the Native AOT analyzer, even if they don’t have the plugin installed.

It also allows for method slots in a VTable to be easily renamed and retyped, using the default Ghidra UI.

Frozen Objects and Strings

Frozen objects like string literals are also annotated automatically. This is nice because it replaces all references to frozen string objects with actual string labels.

Final Words

Native AOT is an interesting next iteration of ahead-of-time compilation in .NET. A lot of people have been using it for performance reasons, but a sizeable portion of (malware) developers also use it as a means to hide the true intentions of their program. However, as we have seen, a lot of metadata is actually still intact, and can be recovered if you know where to look.

The development of this plugin was mainly inspired by having solved Challenge 7 of Flare-On 11. If you’re interested, you can read more about how I solved it in my write-up.

Hopefully this Ghidra plugin tool will be useful to anyone that has Native AOT binaries in their pipeline. And of course, as usual, everything is open source:

If you have any ideas on how to improve it further (such as automatically finding the RTR header), don’t hesitate to reach out.

Happy Hacking!