Addressing Common Misconceptions about .NET in the InfoSec World

Over the past couple years, I have come to know the .NET platform pretty well, from both a developer’s and a reverse engineer’s standpoint.

I can’t always quite say the same about people in the security community.

In fact, more often than not, I encounter a lot of “experts” in the scene (e.g., on Twitter, YouTube, forums, blogs, webinars, talks, chat logs…) that come up with factoids about .NET that are either misleading or just flat-out false. And because they are “experts”, they are often being listened to, which leads to people adopting bad habits/expectations and gives .NET a bad reputation.

I’ve been collecting these “interesting takes” for a good number of months now. Today, I have decided that it is finally time.

xkcd 386: Duty Calls: “What do you want me to do? LEAVE? Then they’ll keep being wrong!”

xkcd 386: Duty Calls: “What do you want me to do? LEAVE? Then they’ll keep being wrong!”

In this post, I will express my frustrations talk about the current state of the scene, and rant about address the most common misconceptions I have come across from a .NET shilling reverse engineering / security perspective.

Table of Contents:

These are the misconceptions/falsehoods/annoyances I will be talking about:

- “.NET is Windows-only”

- “.NET and Mono are the same thing”

- “.NET is closed source”

- “.NET Core is only for Web”

- “.NET is a programming language”

- “.NET binaries use bytecode that is interpreted by a runtime”

- “.NET binaries are easy to decompile and thus easy to analyze”

- “.NET binaries are not “real” binaries and do not contain native code”

- “.NET binaries can be edited using the C# editor of dnSpy”

- “To analyze .NET binaries you need to learn the file format/ECMA-335 document…”

- “Can you add AI to dnSpy so I can start vibe-reversing .NET binaries?”

- “RunDll does not work for .NET DLLs”

- “Check out my new Reflection-based .NET packer/red-team implant…”

- “Here, let me write a YARA rule for this .NET packer…”

“.NET is Windows-only”

Check your calendar; you may be stuck in the early 2000s.

.NET has been cross-platform since 2016 with the introduction of .NET Core. It is officially supported by Microsoft on all major operating systems (Windows, macOS, Linux) on all major platforms/architectures (X86, X64, ARM32, ARM64, WebAssembly…). Additionally, while not originally built by Microsoft, Mono has also existed since 2001 (with v1.0 releasing in 2004), which has always aimed to be a drop-in replacement for non-Windows machines.

.NET may have been Windows-only in its inception, but you really cannot say this anymore in 2026.

“.NET and Mono are the same thing”

.NET is Microsoft’s implementation of the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) specification.

Mono is another implementation of the same specification written independently by Ximian in 2001.

While on the surface both behave very similarly (and in practice are often transparently interchangeable), internally the two implementations share almost no code and have their own standard libraries, quirks, and differences in runtime behavior.

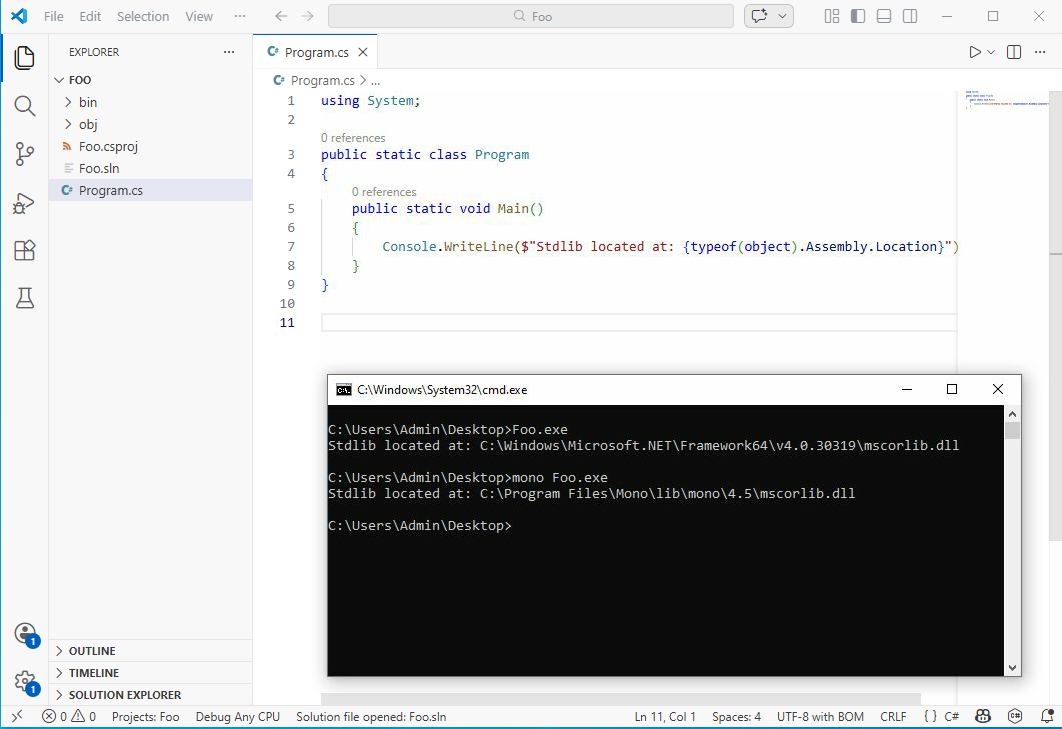

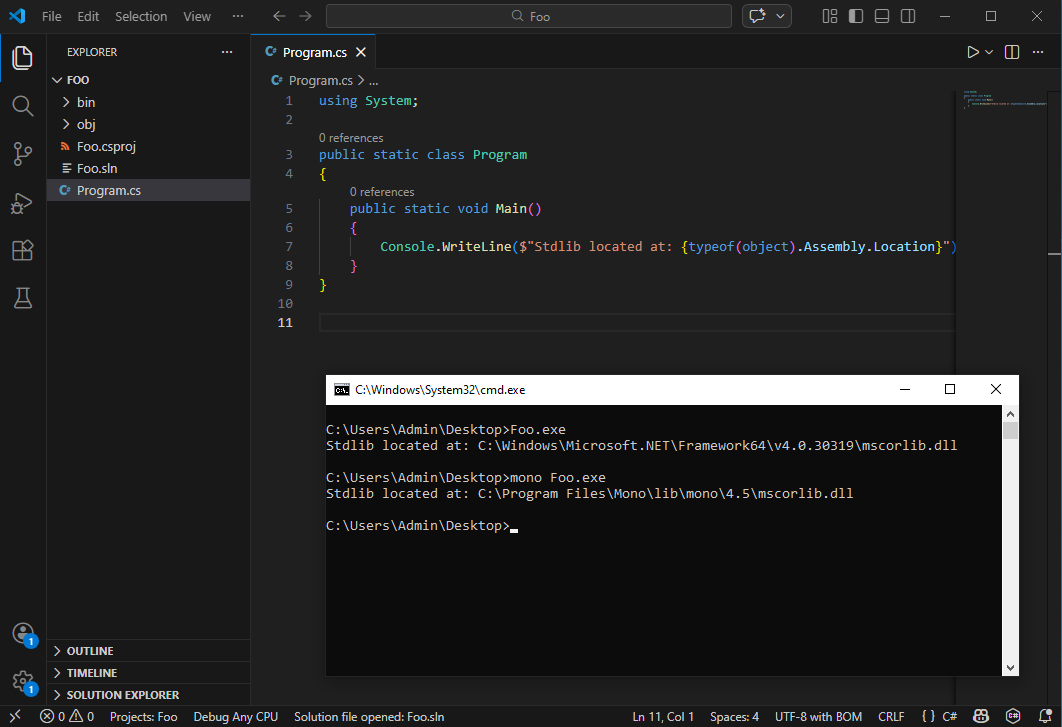

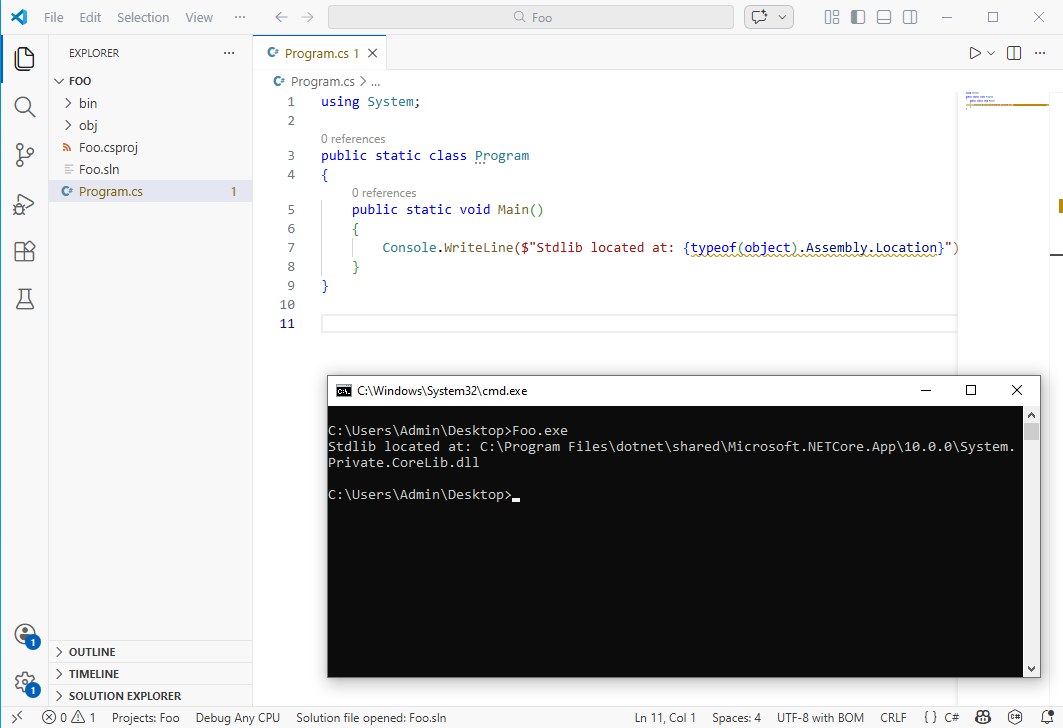

.NET Framework vs Mono on Windows.

.NET Framework vs Mono on Windows.

In the context of malware analysis, you probably will almost never interact with Mono (unless you’re analyzing Unity games or non-Windows malware), mainly because the .NET Framework 4.x is installed by default on most Windows machines, removing the need for Mono to run .NET Framework binaries.

“.NET is closed source”

This is only true for the versions of the .NET Framework that are shipped with Windows.

Nowadays, .NET (just “.NET”, without the “Framework”, formerly known as “.NET Core”) is the de facto and has been open source since 2016, with many contributors outside of Microsoft itself.

Even .NET Framework being closed source is not completely true either. A full reference implementation by Microsoft called the Shared Source Common Language Infrastructure (SSCLI) (also known as “Rotor”) has been available since 2006 and is more-or-less compatible with .NET Framework 1.0 and 2.0. Furthermore, the standard libraries of the .NET Framework are on GitHub. While some internals have changed over time, the overall architecture hasn’t, and it is still an incredibly valuable reference for reverse engineering .NET internals.

“.NET Core is only for Web”

This is only true for ASP.NET Core: the SDK built for writing web applications. .NET Core also exists on desktop, and in the context of security, it plays an important role. Technologies like Single-File AppHost Bundles and Native AOT compilation allow for packaging .NET code into single (statically linked) binaries, significantly complicating reverse and/or detection engineering (see also my previous post on Native AOT binaries).

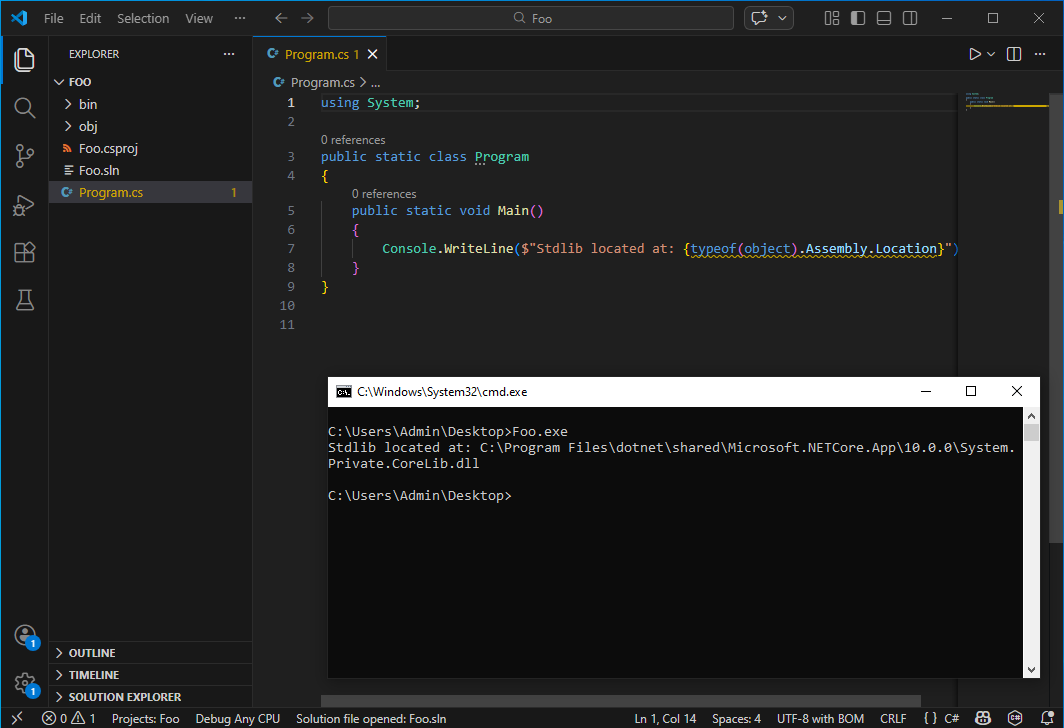

Single-File AppHost in .NET (Core) on Desktop.

Single-File AppHost in .NET (Core) on Desktop.

“.NET is a programming language”

Maybe a bit of a semantics game, but I see it often enough that it probably warrants some attention.

.NET is not a programming language but a platform, i.e., a virtual machine with a dedicated instruction set architecture. Various programming languages (e.g., C#, VB.NET, F#…) target this platform. The closest thing would be the Common Intermediate Language (CIL, sometimes also referred to as IL or MSIL), which is the bytecode that the machine executes and all other .NET programming languages first compile to.

I’ve also heard some malware experts say .NET is a hybrid language… like what does that even mean?

“.NET binaries use bytecode that is interpreted by a runtime”

I don’t know where this misconception comes from, but I see this claim all the time. My guess is that the confusion comes from .NET featuring a bytecode (CIL), and when people say bytecode, they will immediately think of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), which comes with an interpreter in most implementations.

)

This is how I feel infosec people look at .NET

)

This is how I feel infosec people look at .NET

Since v1.0 (2002), the .NET Framework has not interpreted but always executed code through a JIT compiler (as can be seen in the SSCLI 1.0 repo). A JIT compiler translates the bytecode into native machine code on the fly the moment a function is called for the first time. This machine code behaves in the same way as any other native code (and can also be debugged and decompiled). It is also one of the main reasons why it is much faster than an interpreter (perhaps another misconception: .NET is not slow!).

Only since .NET Core (2016) has it featured other types of execution, including an interpreter for some architectures that cannot support dynamic code generation (e.g., iOS and WebAssembly), and some other implementations (e.g., Mono) also feature an interpreter. However, you will never see this enabled on desktop or server applications unless it is absolutely necessary. The funny part is, even most implementations of the JVM also default to a JIT.

Stop saying .NET is interpreted!

“.NET binaries are easy to decompile and thus easy to analyze”

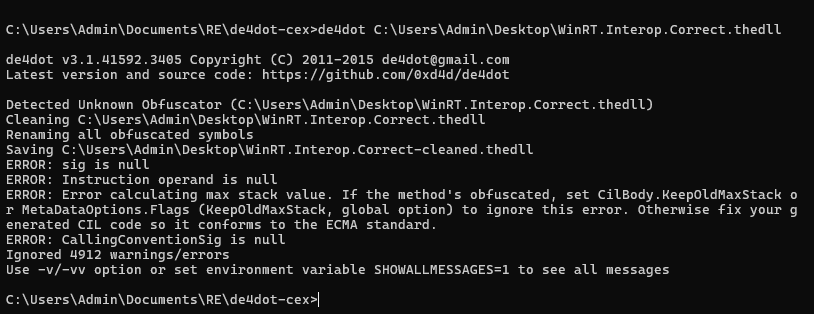

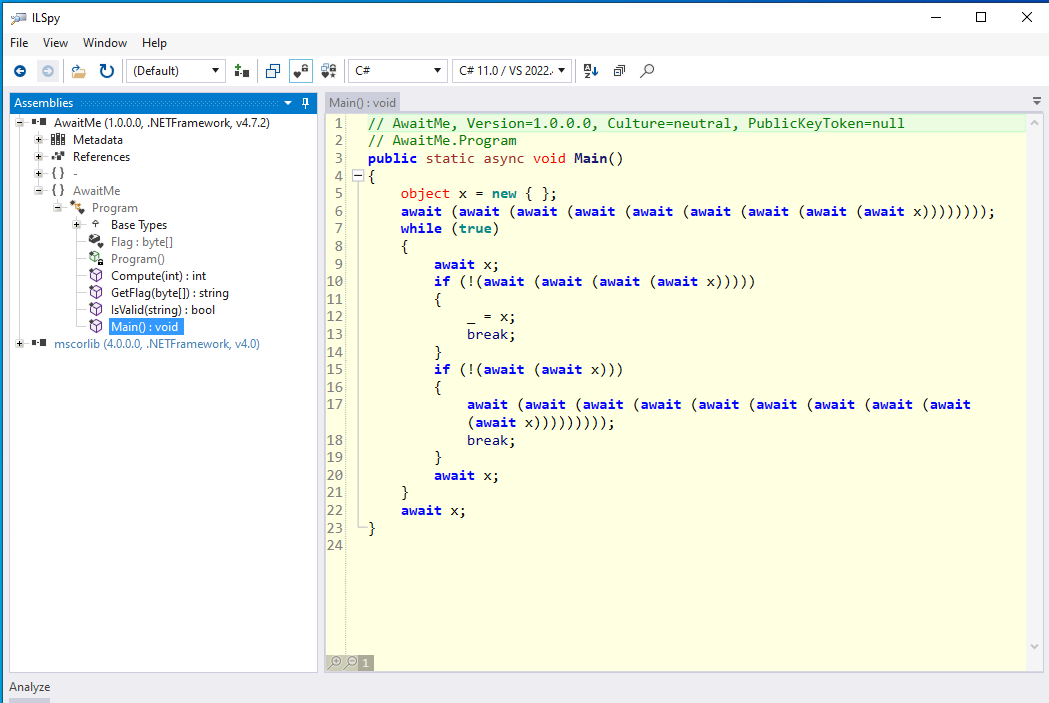

It is true that decompilation is more or less a solved problem for .NET with decompiler engines like ILSpy. Additionally, most off-the-shelf commercial obfuscators also kind of suck, are uncreative, and imitate each other, which directly contributes to the success of deobfuscators like de4dot.

However, even with perfect decompilation, have fun trying to reverse engineer a binary for which de4dot doesn’t work!

Binaries featuring lots of arithmetic and control flow obfuscation, complex virtual machines (e.g., KoiVM, VMProtect), or deep JIT hooks (e.g., DNGuard) are to this day still largely unsolved problems and often require specialized knowledge and/or custom tooling for each scenario. Decompilers also often assume well-formed binaries with predictable structures and break down with unconventional patterns or can even lie if code is maliciously crafted. Finally, .NET is a complex beast, with many features and implementation details, making it often hard to see the forest from the trees.

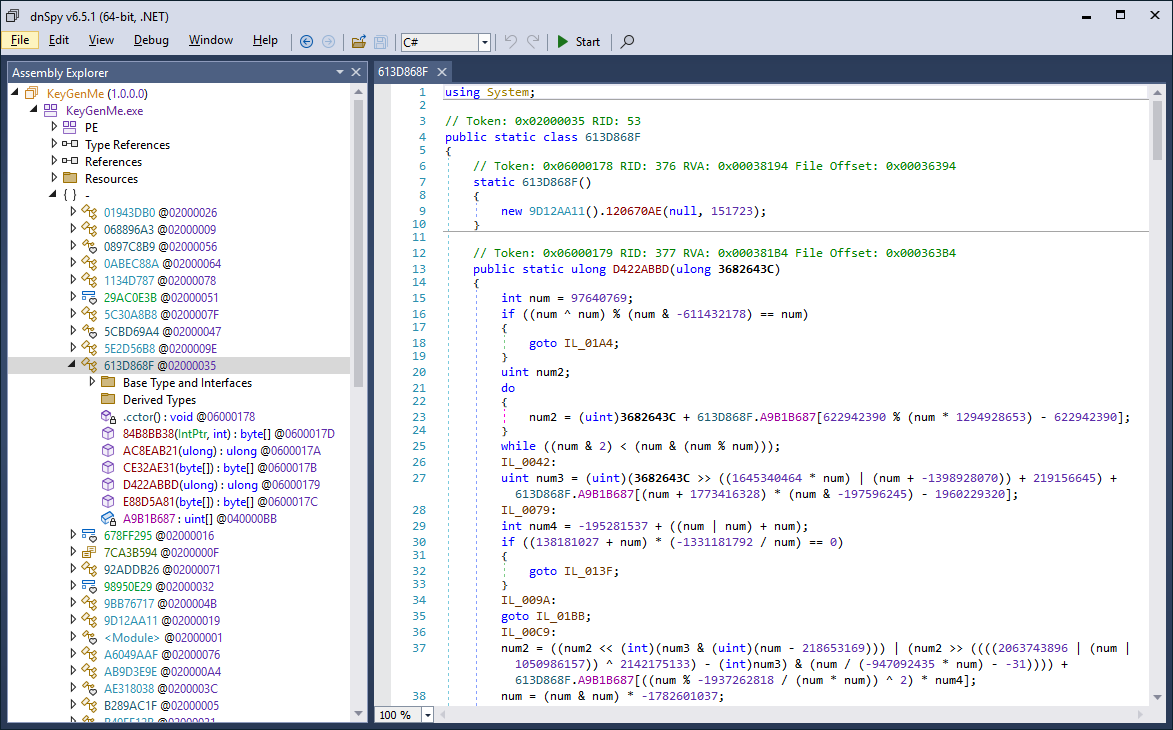

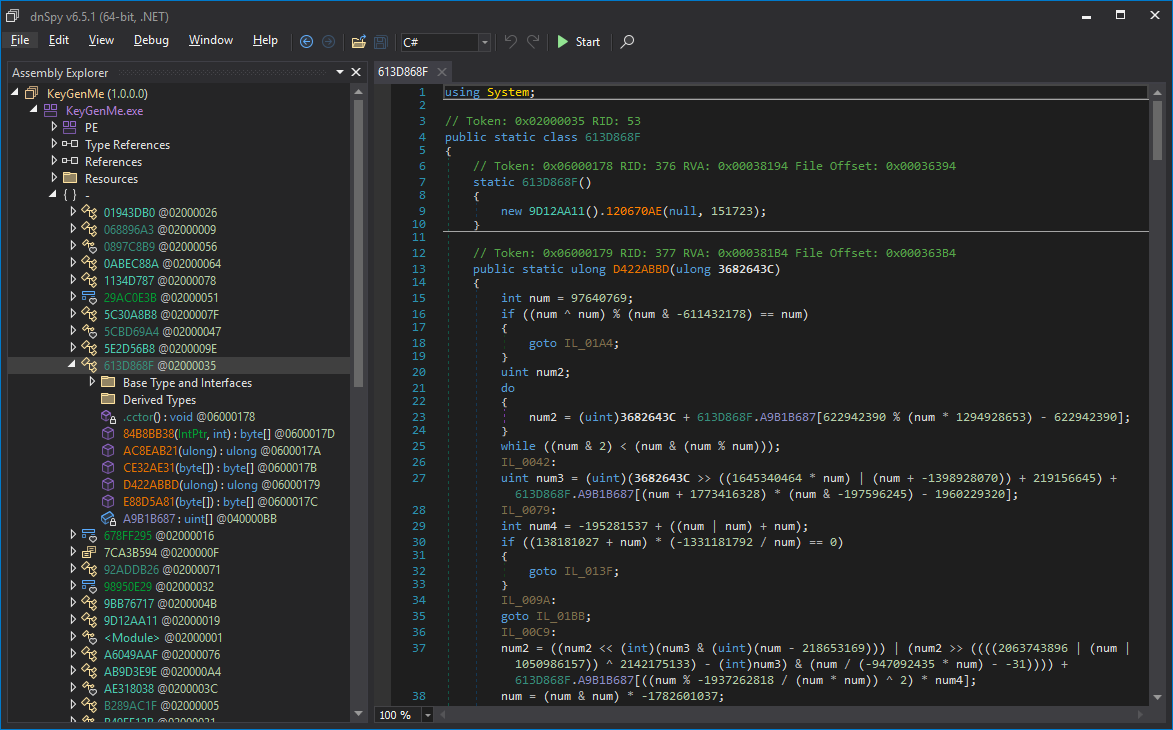

VMProtect .NET Virtual Machine

VMProtect .NET Virtual Machine

It’s always so funny to me that the people that swear by “.NET malware is easy” typically seem to struggle the most when they get a .NET binary that is ever so slightly out of the norm. The irony :).

Don’t underestimate .NET obfuscation!

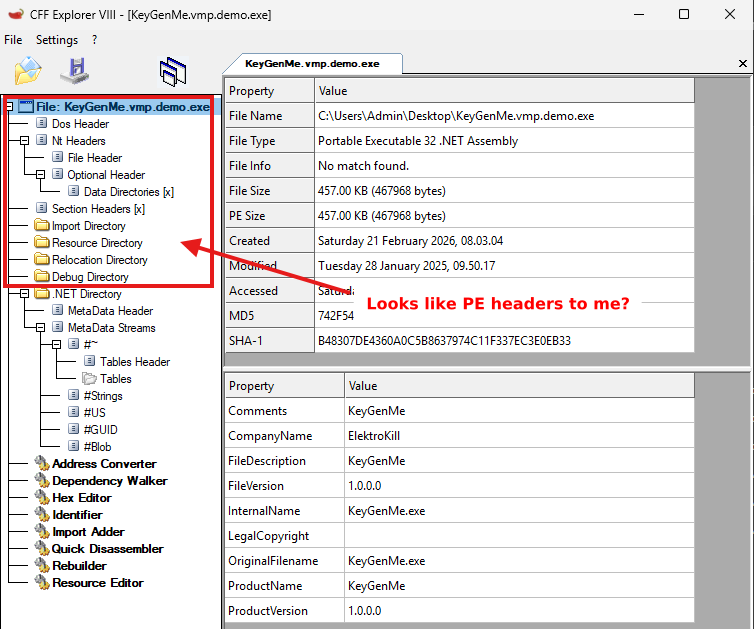

“.NET binaries are not “real” binaries and do not contain native code”

Yes they are.

.NET binaries are normal PE files with normal PE headers, sections, import and export data directories, are mapped by the Windows PE loader, can have a native entry point, and thus can contain native code.

Look like normal headers to me.

Look like normal headers to me.

It just typically does not happen in “normal” .NET binaries that all features of PE are used, because most people targeting .NET write their code in C#, which always produces managed code written in CIL. Malware is not a typical binary though, and often employs a plethora of tricks to hide itself from an analyst.

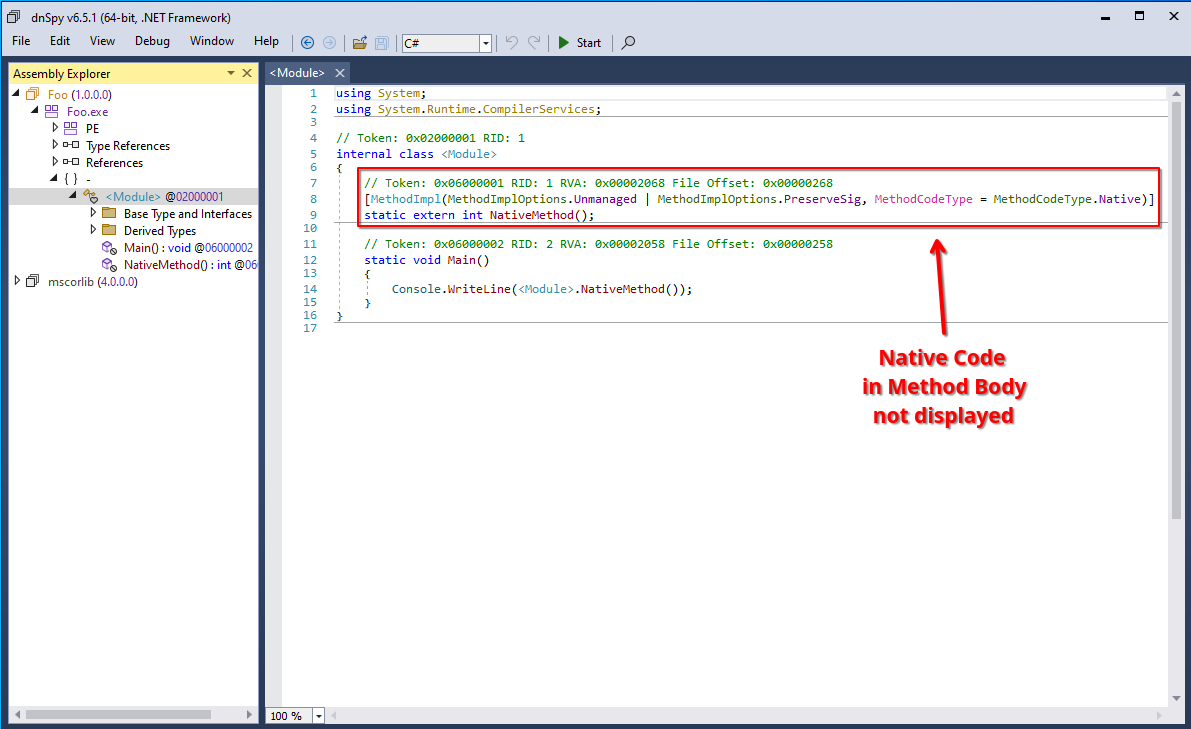

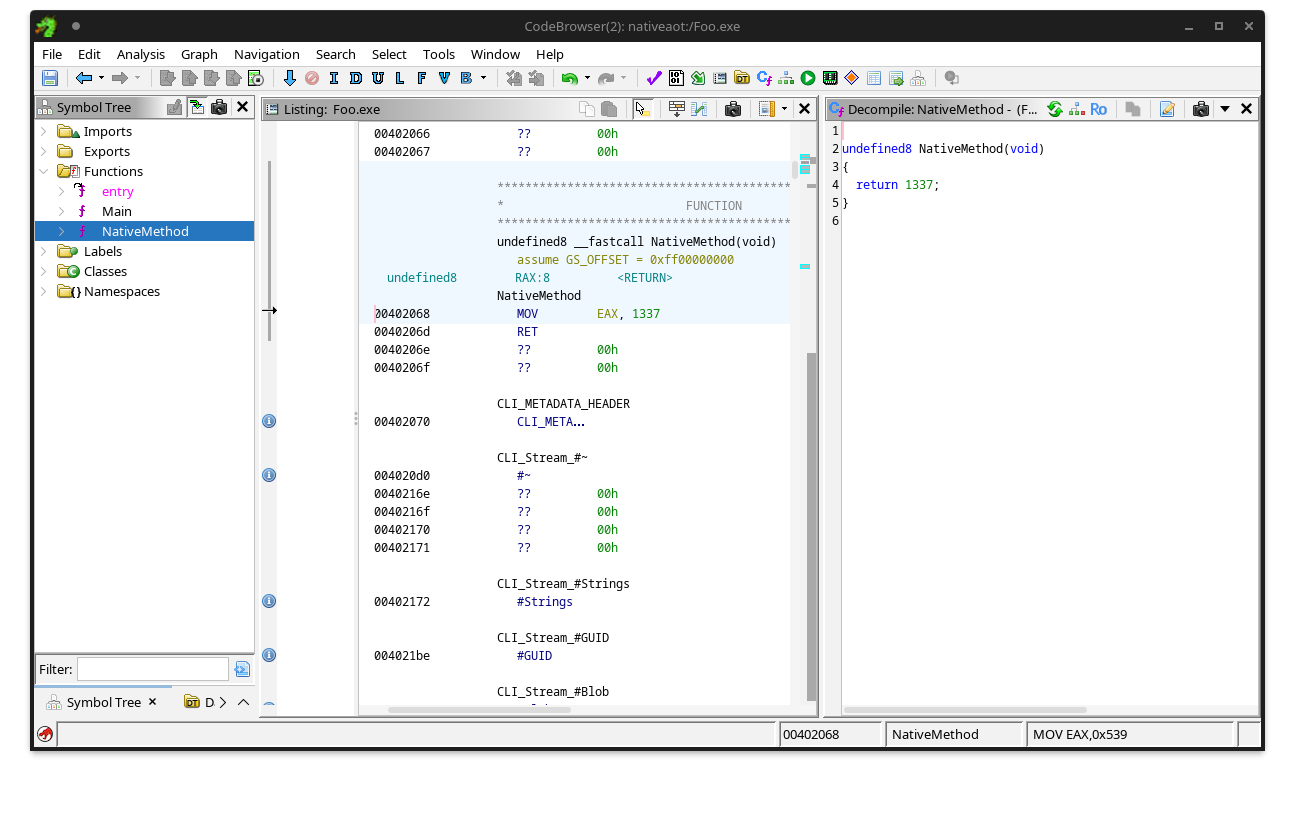

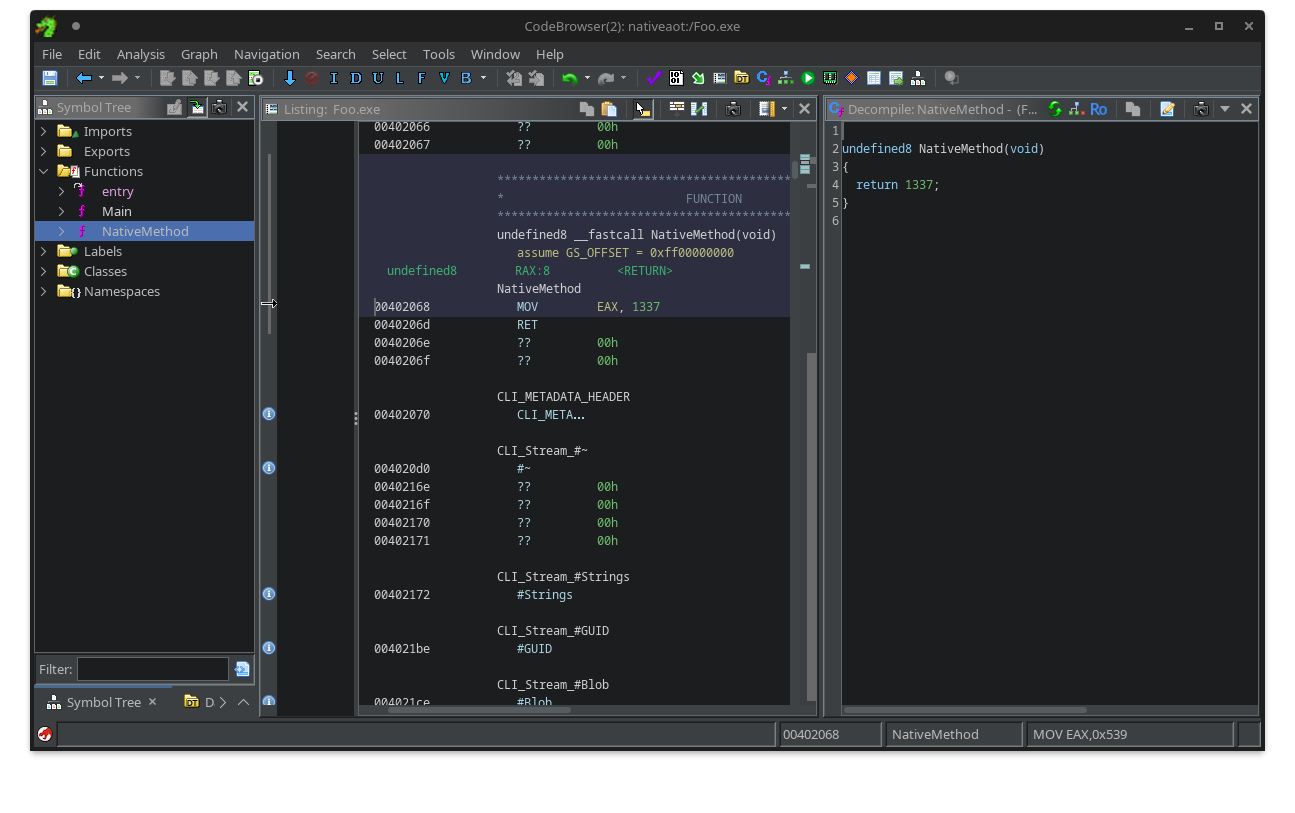

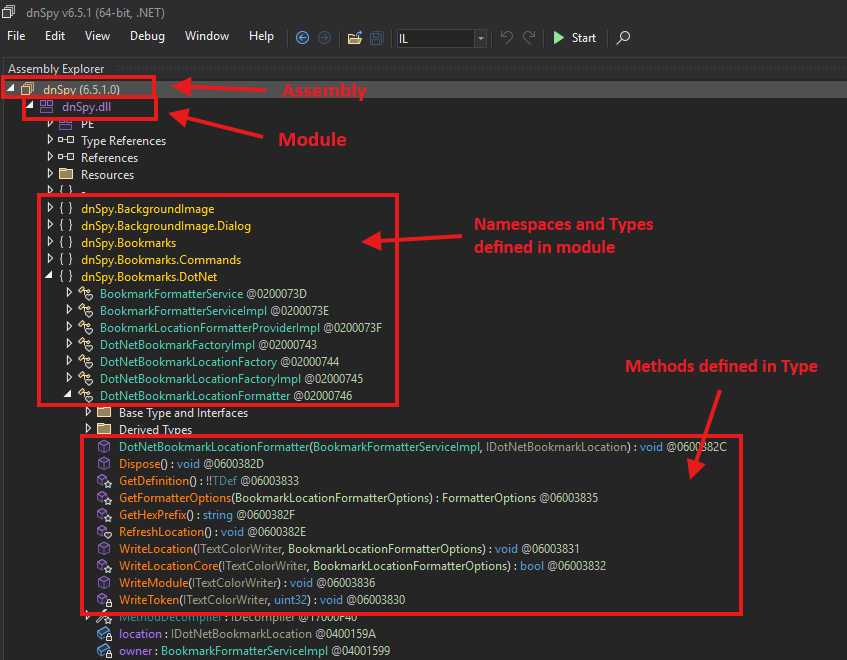

A native method displayed in dnSpy.

A native method displayed in dnSpy.

Prominent examples of these “mixed-mode” assemblies are binaries built using the C++/CLI SDK or obfuscated binaries produced by e.g., ConfuserEx that sometimes emit native code to hide it from decompilers. You can also have a look at my previous post on entry points of a .NET binary.

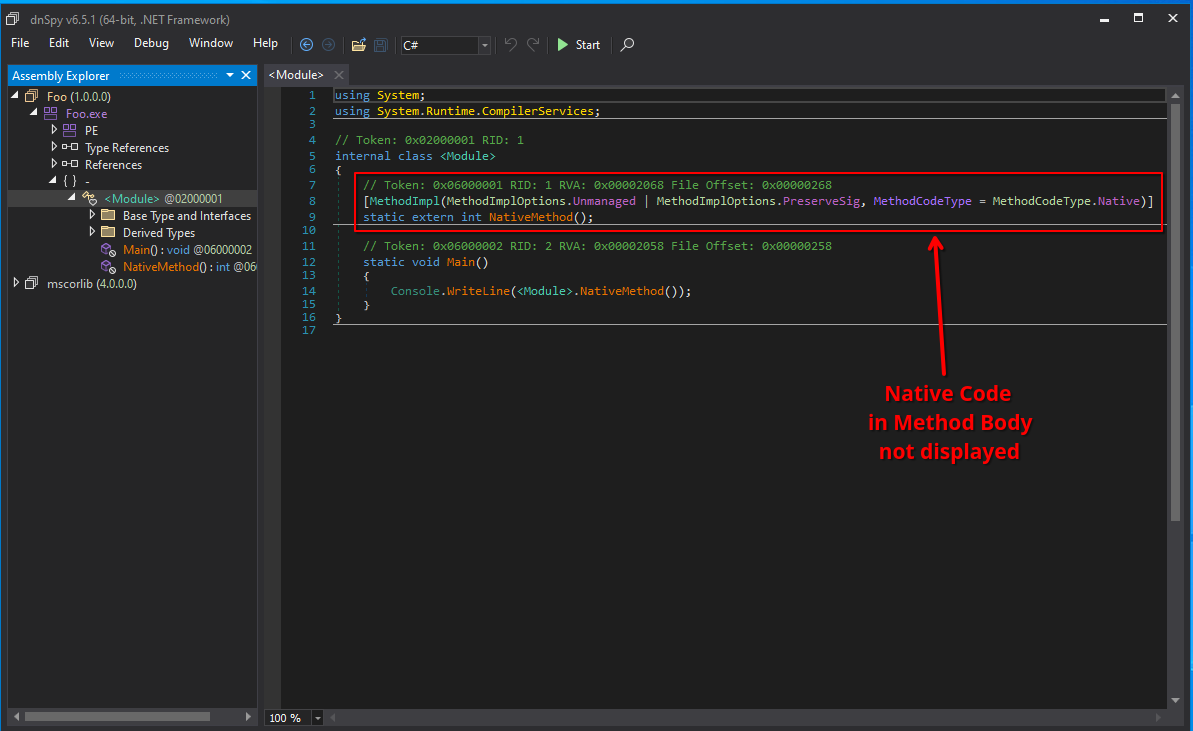

By the way, this native code, while not visible in a .NET decompiler, is perfectly visible in any other native decompiler and debugger:

The same native method displayed in Ghidra.

The same native method displayed in Ghidra.

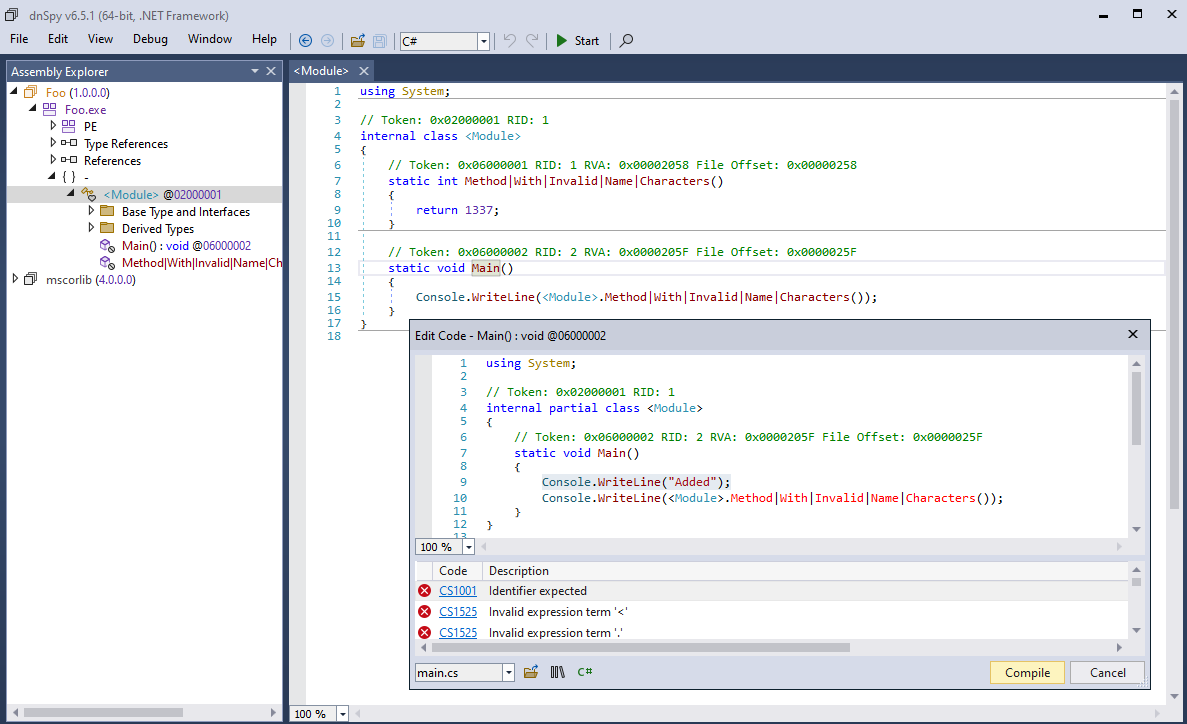

“.NET binaries can be edited using the C# editor of dnSpy”

The first rule of using dnSpy is: You do not use the C# editor of dnSpy.

The second rule of using dnSpy is: You do NOT use the C# editor of dnSpy.

It’s truly a bad idea.

The C# editor heavily relies on the correctness of the decompiler output. Don’t get me wrong, ILSpy’s engine is great and dnSpy does a great job using it, but decompilation remains an imperfect process. Especially with obfuscation at play, a decompiler is very likely to not produce 100% correct or semantically equivalent code. Even if you changed nothing in the decompiled code and you hit compile, you are not guaranteed to have the same behavior as the original method. Furthermore, the feature has been the source of many unpredictable side-effects and/or bugs throughout the years (e.g., #177, #277, #278, #395, #441, #444, #460, #468), making it a pain to use. This is not really dnSpy’s fault; it is just an inherent limitation of any decompilation-based code editing.

Limits of the C# editor in dnSpy.

Limits of the C# editor in dnSpy.

Please don’t use dnSpy’s C# editor.

… and for the love of God, please stop recommending it!

It will only teach you bad habits and make you reliant on something that doesn’t do the thing you want it to do half of the time.

What you should do is get familiar with CIL, the underlying bytecode the decompiled code was based on, and use the IL editor instead. Not only is it 100% reliable and prevents incorrect decompiler artifacts from sneaking in, you will also lay a good foundation for making tools that solely operate on this level of abstraction, which will be required for more complicated cases (e.g., deobfuscation). Also, stop being lazy; CIL is really not a hard language to learn. It’s a very basic stack machine; you don’t need to know about registers, calling conventions, stack memory, etc.

If it were up to me, I would have removed this footgun from dnSpy a long time ago :).

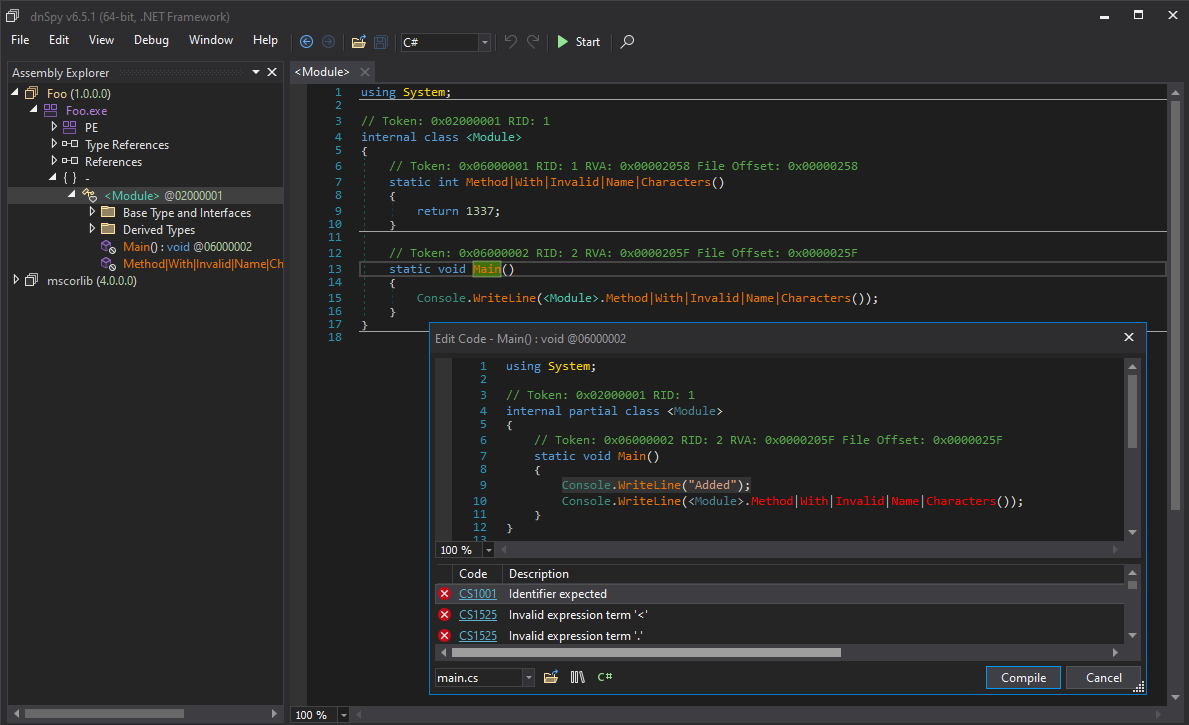

“To analyze .NET binaries you need to learn the file format/ECMA-335 document…”

Oh boy… rant incoming…

Yes, there is a pretty complicated file format, with tables, metadata streams, heaps, tokens, blobs, and what not.

No you don’t need to know any of it, like at all. Maybe like 5% tops.

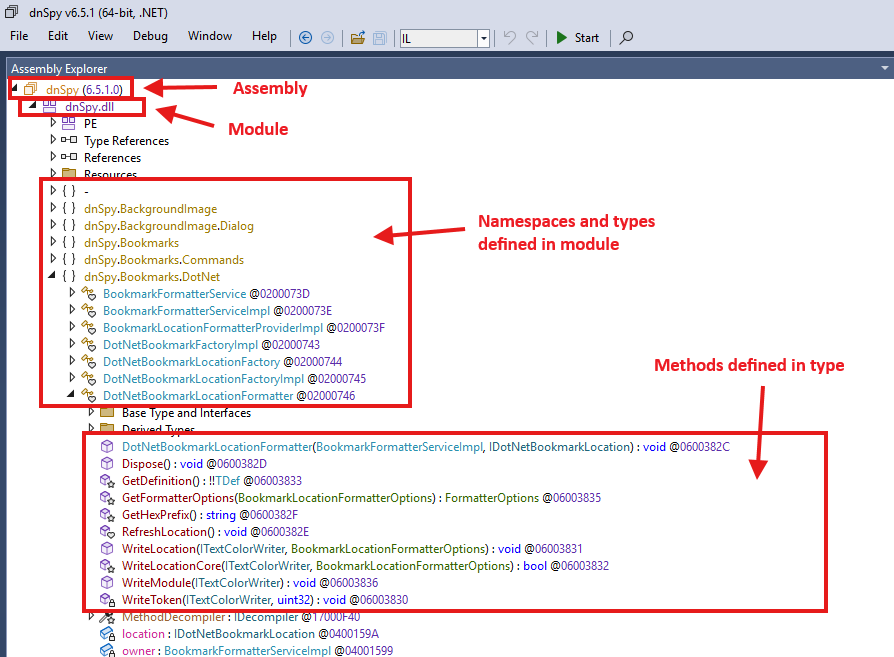

The only things you need to know conceptually:

- Every .NET binary starts with an Assembly/Module.

- Modules define types.

- Types define methods.

- Methods contain instructions.

Example anatomy of a .NET binary.

Example anatomy of a .NET binary.

Everything else is just extra stuff that in 98.9% of usecases[citation needed], you should not really need or want to care about any of that.

I have seen a lot of people in infosec that fall into this trap, particularly people that only know Python. For better or worse, the reverse engineering world primarily runs on Python, and as such, there are a good number of Python libraries that implement some form of .NET binary parsing (e.g., dnfile, dncil, dotnetfile…).

With all due respect to the original authors, these Python libraries all are vastly inferior to what is actually available and used in .NET binary processing, and I put a lot of the blame on them for this misconception. Here are the main issues I have with these libraries:

- They only present raw data, e.g., raw tables, blob bytes, indices and tokens.

- They are read-only, meaning you cannot use them for anything other than extracting things.

- In practice, they are (very!) often inconsistent with the runtime in how they actually parse a binary, and break on maliciously crafted ones.

Whether you are writing a config extractor or a full deobfuscator, you will always end up following metadata tokens and indices, parsing blob signatures, resolving assemblies and types, etc… Doing all this correctly requires a very thorough understanding of the ECMA-335 specification, and even the more well-versed get it wrong frequently (including myself!). I have seen people recommend this document many times as a “starting point”. If you ask me, this is terrible advice. Unless you need something very specific, you should not even think about opening this document pretty much ever.

Luckily, you don’t have to! Tooling for .NET RE has matured so much that all major libraries that do have a more sane higher-level API (e.g., Mono.Cecil, dnlib or AsmResolver, shameless self-plug I know, sue me) have implemented this all for you correctly, and abstracted it away into a DOM-like representation, similar to how you’d see it in a decompiler.

You want to find the method called StringDecryptor.Decrypt(string) in a File.exe and iterate through its instructions?

Don’t go to the metadata tables and 50 pages deep into specification documents. Just walk the DOM tree:

- Open the assembly file.

- Find the

StringDecryptortype. - Find the

Decryptmethod with a single parameter of typeSystem.String. - Loop over all the method’s instructions.

In code, depending on your library of choice, that would look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

using AsmResolver.DotNet;

var module = ModuleDefinition.FromFile(@"C:\Path\To\File.exe");

var type = module.TopLevelTypes.First(t => t.Name == "StringDecryptor");

var method = type.Methods.First(m =>

m.Name == "Decrypt"

&& m.Parameters.Select(p => p.ParameterType.FullName).ToList() is ["System.String"]

);

foreach (var instruction in method.CilMethodBody.Instructions)

Console.WriteLine(instruction);

No manual parsing of tables, blob signatures, tokens… Just intuitive objects reconstructed by your parser. Let libraries help you!

The only issue with this approach, is that these “good” libraries are all written in C#. For some reason, this makes a lot of infosec people visibly repulse.

This is how I feel most infosec people think about .NET binary processing programmatically.

This is how I feel most infosec people think about .NET binary processing programmatically.

Even if you really didn’t want to use C#, you can still use Python and use the library by installing pythonnet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import clr

clr.AddReference("AsmResolver.DotNet") # Requires the library in the same directory as the script.

from AsmResolver.DotNet import ModuleDefinition

module = ModuleDefinition.FromFile("C:\\Path\\To\\File.exe")

type = next(t for t in module.TopLevelTypes if t.Name == "StringDecryptor")

method = next(

m for m in type.Methods

if m.Name == "Decrypt"

and [p.ParameterType.FullName for p in m.Parameters] == ["System.String"]

)

for instruction in method.CilMethodBody.Instructions:

print(instruction)

An equivalent version of the same script using Python will require a lot more code to manually follow indices, resolve the type and method names, parse the method signatures, and decode and format all CIL instructions.

Note that, even though it may seem like it, I am really not trying to bash on any of the Python libraries, nor am I necessarily trying to advertise my own library. I do recognize that not every workflow can use C# or has the liberty to set up python-net. Also, sometimes you do actually need the low level stuff (though the C# libraries also provide you with options for that…). I am simply saying that the Python implementations are not as mature as the C# options, are often incorrect or incomplete, and make things harder than they could be.

My opinion is that if you’re working with lots of raw metadata tables, tokens, string indices, and blob signatures, you are very likely doing something wrong.

“Can you add AI to dnSpy so I can start vibe-reversing .NET binaries?”

The number of times I’ve been asked if I know of an MCP plugin for dnSpy or whether I could make one…

Firstly, I am not a core dnSpy(Ex) maintainer. Yes, I have contributed to the project before. No, I have no intentions of adding AI to it. Stop asking me for it!

But more importantly: stop asking the actual maintainer for it!

They are not interested in it, and I think they are right not to be interested in it.

- It adds a lot of maintenance burden to an already very large project that could have easily been a commercial product but is open source instead. Keep in mind the project is singlehandedly being kept alive by one person with a life outside the internet.

- It is not a core feature of a .NET decompiler / debugging tool. Yes, it may be useful, great as an additional plugin that you can install alongside. No, not everyone wants it.

Zooming out for a second, for some reason this AI hype train has caused everyone to think everything needs AI chatbot integration now. Even Windows Notepad has AI integrated nowadays (yes, Microsoft decided that thing that is essentially just a textbox in a movable dialog needed AI for some reason), which also hilariously led to a RCE vulnerability sneaking in this month. What a time to be alive in! Windows Notepad is vulnerable to command injection; can you actually believe it?

I have also come to notice AI has made people lazy.

People don’t want to do research themselves anymore and settle for mediocre. Maybe it is me getting old, but it blows my mind that people’s first instinct for looking up something on the internet is having an AI chatbot hallucinate a summary on the keywords, rather than going to a search engine and considering the facts yourself. It gets worse, when the AI is inevitably wrong one day, people are completely clueless on what to do. I no joke have been asked multiple times:

“Hey I have this binary and I cannot make sense of it. I tried [insert LLM name] but it didn’t work. Do you have recommendations for other LLMs that do work?”

To me, it shows a clear lack of understanding of the problem you are trying to solve, and frankly, if you are asking me this genuinely, you should maybe consider doing something else in life.

Back to dnSpy and vibe coding/reversing: The other day, dnSpyEx did in fact receive a pull-request to add MCP support to the main client. It was completely vibe-coded, full of hallucinations, broken code, and cursed string-based operations on things that can be expressed in nice, reliable, non-fuzzy structured data. It blows my mind people think this is acceptable behavior. Dumping a whole truck of slop code on a maintainer for PR review is not contributing, it’s wasting people’s time (and your tokens).

My opinion: generated AI code + no care for correctness/quality = gtfo.

My opinion: generated AI code + no care for correctness/quality = gtfo.

If you really must use AI, go find some MCP plugin on GitHub or write/vibe one yourself. Don’t bother the dnSpy maintainers with it.

“RunDll does not work for .NET DLLs”

Correct.

But fear not, we have something way better. It’s called Reflection.

Just drop the following C# snippet into a Program.cs and use it to call literally any function (public or private) in the binary:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

using System.Reflection;

var result = Assembly.LoadFrom(@"C:\Path\To\File.dll")

.GetType("SomeNamespace.StringDecryptor")

.GetMethod(

name: "DecryptString",

types: [typeof(int), typeof(string), ...],

bindingAttr: (BindingFlags)(-1) /* include all members */)

.Invoke(

obj: null,

parameters: [1337, "foo", ...]

);

Console.WriteLine(result);

Just make sure you keep types in sync with parameters, and that you use the same target framework version as the DLL you are trying to call.

This works great for things like quickly deobfuscating strings dynamically.

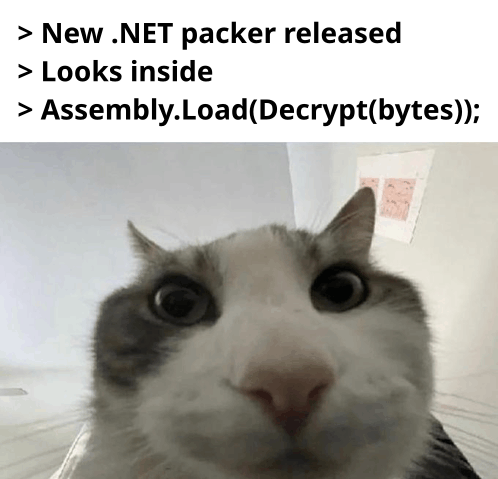

“Check out my new Reflection-based .NET packer/red-team implant…”

Speaking of Reflection…

Literally me with 99% of all .NET packers out there.

Literally me with 99% of all .NET packers out there.

No, using Assembly.Load(<bytes>) is not novel.

No, the use of RuntimeAssembly.nLoadImage does not count.

Neither does your custom CLR hoster stub that is written in C++ and uses ICorRuntimeHost.

No, it does not matter where in the PE you store it or whether you used AES or RC4.

We have known about .NET reflective loading as a packing mechanism for the past 10-20 years.

It’s not an exploit; it’s a feature of the runtime.

Every obfuscator from the Stone Ages knows about it (even the shitty commercial ones that all just imitate each other).

Which is also why we all know how to deal with it (e.g., setting a breakpoint on Assembly.Load or dumping the module using dnSpy, WinDBG or any off-the-shelf dumper on GitHub).

It’s cool that you’re working with .NET and exploring all its features. I don’t even mind you writing about it! I support you in continuing this journey. Let’s just not pretend it is the next generation of crypters/packers/red-team implants/EDR bypasses/AMSI bypasses/whachamacallits… please. It’s getting old.

“Here, let me write a YARA rule for this .NET packer…”

This may be one of the worst offenders, also because it has direct implications on the quality of our security tooling.

A lot of rules I encounter are really bad! :)

I partially blame the #100DaysOfYara trend. I understand the idea is to have people write many YARA rules for practice. However, the amount of garbage that enters our community because of it is astounding. The rules I come across that are specifically written for .NET binaries often either do not work at all, or work so well they flag everything as malicious.

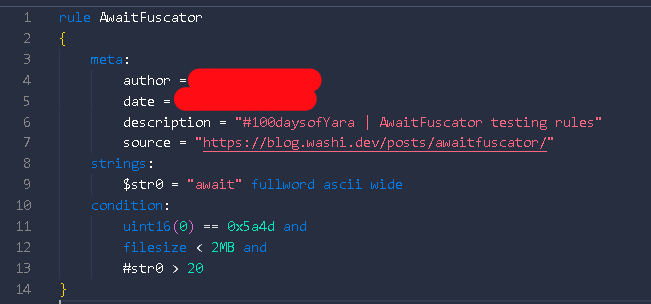

To showcase how hilarious it can get, here is an example. Some time ago, I wrote a toy obfuscator called Awaitfuscator, which transforms your C# code into a bunch of await expressions.

It’s a dumb project, completely impractical, easily defeated, but also really funny.

I encourage you to take a look at it if you are interested.

Others were also interested, and some of them were infosec people trying to write YARA rules for it. I came across this one from a very highly respected senior security researcher with many followers (30k+), with many DEFCON/BLACKHAT/etc talks to his name:

A rule that is supposed to match Awaitfuscator protected binaries.

A rule that is supposed to match Awaitfuscator protected binaries.

Eh….?

If it isn’t obvious, this doesn’t work because:

- An

awaitexpression is syntax sugar for control flow: it gets compiled away into normal branch instructions. Just because it spells outawaitin the source code, does not mean it will appear as an ASCII string in the file. Do people think the C# compiler embeds the source code in the final binary or something? - Even if it did do that, there are so many programs that use the

async/awaitparadigm that this would just be a really bad rule. It is pretty normal for a decently-sized program to have a couple ofawaitkeyword occurrences. This would end up flagging everything.

It is a clear showing of a lack of understanding of how .NET binaries are constructed. Needless to say, it didn’t even work on the sample binary that I provided in the original post.

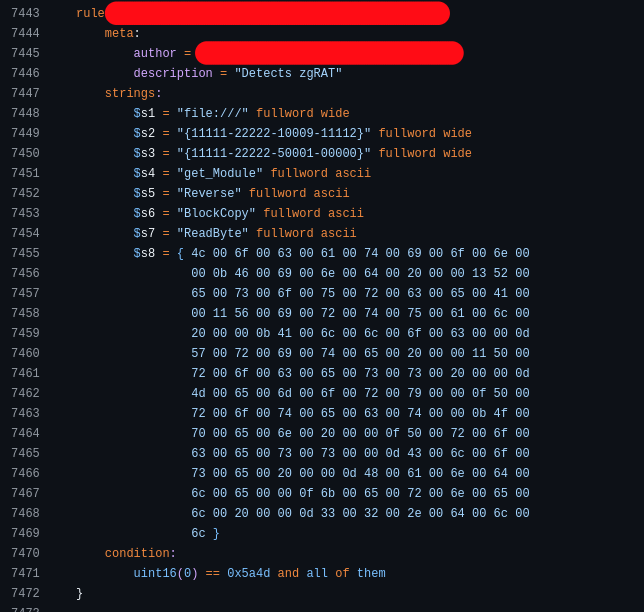

The worst part is that despite the low quality of these rules, they are often still adopted or taken as good examples. Here is another one that shows a gap in the fundamental understanding of .NET binaries, used in a good amount of “vetted” YARA rule collections:

A rule that is supposed to match zgRAT binaries.

A rule that is supposed to match zgRAT binaries.

The huge binary blob is already hilarious, but regardless, these strings are not characterizing just zgRAT but any binary protected using .NET Reactor, a popular code obfuscator for .NET that zgRAT just so happens to use.

This results in you basically flagging all binaries protected by this packer, including legitimate software.

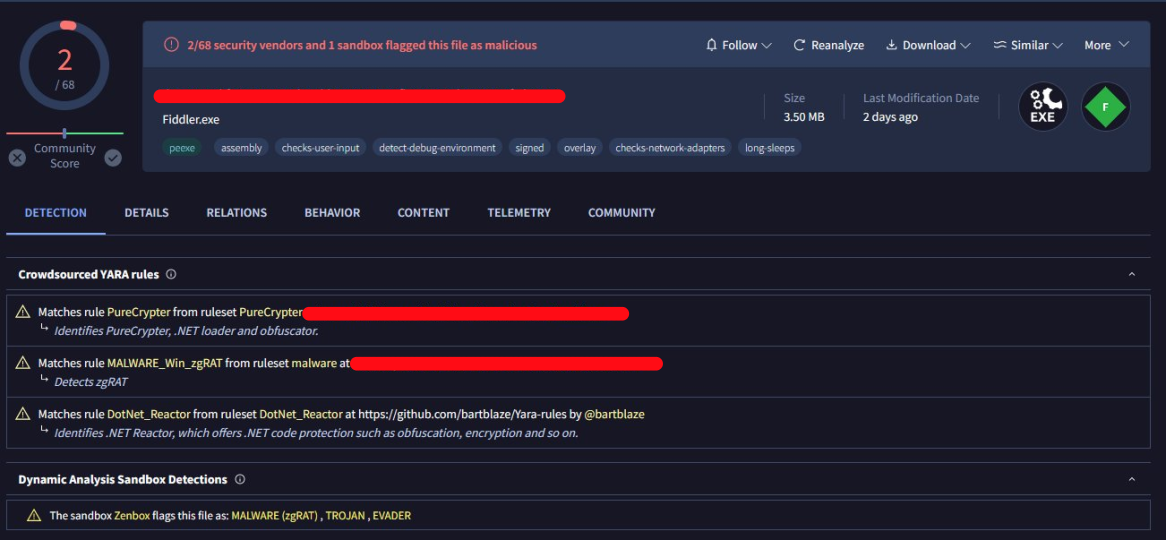

Here, for example, is a version of Fiddler marked as malicious by these “crowdsourced rules” because it is also protected by .NET Reactor:

Screenshot courtesy of @cod3nym

Screenshot courtesy of @cod3nym

Funnily enough, there is apparently another “crowdsourced rule” marking it as PureCrypter. Probably an equally bad rule, if not worse.

I am not necessarily bashing #100DaysOfYara (well… maybe a little bit :)), nor am I trying to discourage people from participating in it or expecting newbies to write perfect rules.

It is just interesting to me that experts always tell you not to include UPX or VMProtect strings for malware detection, but as soon as we talk about a .NET binary, this knowledge seems to completely evaporate in thin air.

And because the rule is written by an “expert”, it gets adopted quickly with little thought.

The lack of quality control that I am observing is very apparent.

Final Words

It is fine not knowing things. It truly is! There are a lot of things I don’t know either!

I also make sure I don’t talk as much about things I don’t know much about.

Not knowing about a topic becomes a problem when you are acting like you do, and spread with a (false) level of confidence information that is just really low quality or straight up false. Especially when you have a bit of a following, it can become dangerous as there will be a lot of people listening to you and following your “advice”. Note that I am not saying you can never be wrong either. Just make sure you also own your mistakes and correct the record when pointed out as such. Too often do I see this not happening either.

Some of these “experts” hedge upfront (or afterward) that they are not actually experts on the topic, yet still proceed to act like one (“Oh I am not an expert, but here is also an essay on how it works / why you’re wrong…”). This is arguably the worst version of them all, and it frustrates me to no end. It is pretentious, disingenuous, and unjustifiably excuses you from, in my opinion, wrong behavior.

If I implicated you in some way or another with this post, know also that I don’t mean to personally attack you. But please, read up on the topic before you post about it, or don’t post at all.

Thank you!